Having grown up in the U.S., I used to think American cities were universal. The glass rectangles piled on top of each other, the glossy towers jutting up like angry glistening phalli, the barrage of bleating car horns, the unstoppable society of emboldened rats, the concrete chaos, the grime—that was it; that was just what cities looked like.

But since visiting cities older than the United States itself—and living in cities well over a thousand years old—I began to notice two characteristics common (though not exclusive) to American cities. First and obvious: they’re abominable. Between the buildings, the roads, the billboards, the cars, the facades, and the decay, they’re just objectively ugly spaces. Some older American cities are exceptions: iconic gems like Detroit, New Orleans, and New York (except for Midtown). But most American cities weren’t built to look nice or provide enjoyment for the people living in them; they were built to minimize construction costs and maximize developers’ returns on investment. In short, these cities were built to serve the bank accounts of a few rich men.

The second characteristic is less immediately apparent than ugliness, but it’s more intrusive in the long run. American cities can be difficult for living bodies to inhabit. The air is poor, the scale is off, the smells unpleasant, green spaces scarce, parking lots abundant, housing isolating and unaffordable, bars too loud, cafes too small, shopping centers too big, offices too cold, streets too hot, transportation inefficient or inaccessible, and plus, everything is violently unequal along both race and class lines. But looking globally, this is more a matter of youth than Americanness. Most cities under a few centuries old, from China to Brazil, tend to be ugly and brutal places to live. Even older cities are not immune from the encroachment of the hideous and the uncomfortable; at the edges of the Old Town in Edinburgh, Scotland, the grand stone cathedrals, symmetrical townhouses, and intricately-decorated facades intermingle with jarring, unhealthy-looking glass-and-concrete blobs. (This isn’t to suggest there’s no beautiful or humanely designed modern architecture; there most certainly is, it’s just vastly outnumbered by the ugly. Egocentric “starchitects” aside, only a small proportion of new construction even consults architects these days.)

This isn’t just the subjective ravings of a disgruntled expat. Tourists flock in droves to old, beautiful, livable cities like Edinburgh or Venice just to take pictures of stunning ancient buildings, or to stroll down lanes carved out for people instead of cars. Edinburgh has been voted the UK’s happiest city and also named the best city in the world to live. In the meantime, nobody’s booking a vacation to Houston, Texas to admire the gorgeous sprawl.

What drives the harshness of the modern city? A number of factors, including racist politicians, nihilistic architects and planners who put ideology over livability (Robert Moses, cough cough), and ruthless real estate moguls with a mad devotion to commerce and consumption above all else. Cities are the physical embodiment of the values, biases, and power structures of a society and its economy. Ugly, brutal, capitalist America has built ugly, brutal capitalist cities.

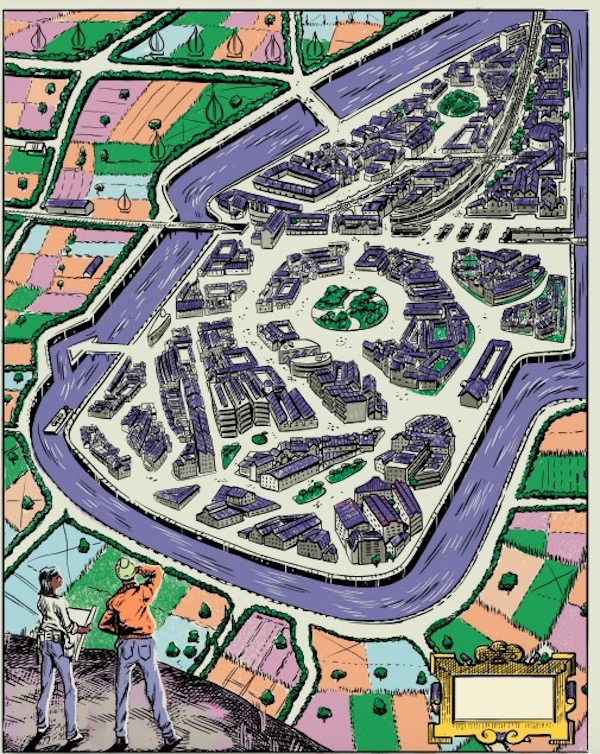

Illustration by Ben Clarkson

But one single commodity is responsible, above all, for the waste and hideousness of our cities: fossil fuels. The modern city is the carbon city. While capitalism and finance, exploitation and working-class grit may have all conspired to physically assemble these cities, it was carbon energy that provided the raw material abundance—the mountains of bricks, the rivers of asphalt—necessary to sprout steel towers and sprawling corridors of commerce.

One recent summer day, on the scorching pavement of New York City, I accidentally strolled through the largest private development project in the world: Hudson Yards in Chelsea. That day, multiple generic-looking glass towers were bursting out of the broken ground. An articulating boom—basically an enclosed platform on a hydraulic arm, sitting atop four huge tires—sat idling next to one of the erupting new towers. As I scowled at the exhaust pouring from the machine—adding more heat to the concrete oven—it suddenly hit me how utterly dependent this and all other such developments are on diesel fuel, coal, and gas. I imagined the oceans of oil, the caves filthy with coal, all needed to light the innards of a skyscraper, to keep its temperature steady, circulate its air, pump water through its copper veins, manufacture and then move its steel bones and glass skin across oceans, hoisting with tall cranes its Frankenstein pieces into the air, elevating people and material up and down its long frame. The World Bank estimates that cities gobble up “as much as 80 percent of energy production worldwide” while the International Energy Agency calculates they spew around 70 percent of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. Cities are the factories of climate change, the engines of our demise.

That’s because today, the only fuels capable of pouring such immense quantities of energy into our cities—both to construct and to sustain them—are the very dense, abundant fuels made from fossilized plants and animals. Hundreds of new cities have been built since the turn of the millennium. The explosion in new metropolises we’re seeing around the world today may be encouraged by the perverse financial incentives of neoliberalization, but it’s been made possible by the fossil fuels flowing through all arteries of the global economy. It’s probably obvious to state that the world’s building boom is fueled by carbon energy. What’s less obvious is what happens when nations decide to shut off the flow of fossil fuels, which they’ll have to do, and soon, or the planet will die.

As we all know, we cannot keep burning fossil fuels. If we do, we will rapidly make earth uninhabitable for complex life, including humans. Volcanoes burning buried fossilized carbon caused the greatest extinction event in earth’s history, the Permian-Triassic extinction, also known as “the Great Dying.” Much deadlier than the asteroid that decimated the dinosaurs, the Great Dying killed most life on earth and in the oceans. Today, we’re burning fossilized carbon ten times faster than those ancient volcanoes did. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report recently stated that we must completely stop emitting carbon by 2050 at the latest. To limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, we have about a single decade to steeply cut emissions (that means whomever is elected president in 2020 will basically get to decide the fate of humanity). And the IPCC report was relatively conservative, meaning we may have even less time. When the entire economy, billions of lives and livelihoods, depend on a resource we have to immediately cease using, fundamental change is no small order. “Decarbonization” is a single word that means monumental disruption.

So what happens when we can no longer use fossil fuels to maintain skyscrapers and sustain sprawling, energy-slurping urban spaces? Well, it means we must build new cities and redesign existing ones from the ground up. Whether the non-carbon sources of energy that we have right now—nuclear, wind, and solar electricity, and some biofuels—could provide the sheer volume of energy that fossil fuels provide and that modern cities crave is debatable. But whether they can do this in the short timeframe we have is not up for debate at all. We can’t just swap in some uranium and solar panels and ethanol and expect our metropolises to chug along exactly as they are while avoiding collapse. And no matter how quickly we decarbonize, the seas are still rising.

The choice before us is not between the status quo and apocalypse, between a thriving Manhattan and watery doom, as much as some Manhattanites might believe otherwise. Sure, as sea levels rise we may have to abandon some of our most treasured cities and build new ones, or refashion existing ones that already sit in safer parts of the country. That doesn’t have to be all bad. In fact it may be a blessing. It offers us a chance to build or rebuild cities that are not only carbon-free and climate resilient, but also more beautiful, humane, and equitable places to live. As we discuss what should be included in a Green New Deal-style policy—the central policy vision of the left at the moment—we should be incorporating plans, values, and funding to build better cities and coordinate the migration of millions. If fascists and feudal capitalists dominate politics this century, then these new and redeveloped cities will reflect their values: authoritarianism, rule by the rich, and violent elimination of the vulnerable. If libertarian ecosocialist values dominate politics, then our cities will reflect those values instead: the sanctity of life, liberty, and equality. The stakes couldn’t be much higher.

Better Cities

It’s important to consider now what the general contours of the decarbonized city could look like. What might constitute the best outcomes for the people living in them (and outside of them)? For a little inspiration, we can look at preindustrial cities, which were built before fossil-fueled machines existed. While many old cities are beautiful, they could also be spaces of inequality, squalor, and disease. It’s important to note here that while a decarbonized city can borrow from some of the best qualities of ancient urban spaces, it doesn’t need to include open cesspits for historical accuracy. We can easily incorporate modern comforts like hygienic plumbing, electricity, and trains. Decarbonization doesn’t mean deprivation or giving up the most important technologies that make modern city life safe and hospitable. To the contrary, it can make cities far more abundant in the things—fun, equality, beauty, space—that matter most.

Aside from the design and basic quality-of-life issues that can be improved by decarbonizing cities, perhaps the most important question is whether they could be more equitable than carbon cities. Looking to pre-industrial examples doesn’t give much indication. Many cities of antiquity were built on slave economies and could be brutally stratified, while others were quite egalitarian. Archaeologist David Wengrow goes further to suggest that “cities organised ‘from the bottom up’ and on relatively egalitarian principles can be found at the very basis of urban civilisation in Eurasia.” Stephanie Webb, co-founder of the project Decipher City, suggested that building equality into non-carbon cities isn’t a linear relationship. That is, we don’t just decarbonize and then decide to build equality into that. “As long as legitimate, intersectional coalitions are built that work to dismantle segregation, which has been the unspoken impetus for urban sprawl, then a carbon neutral-society can be built.” Not only will decarbonization provide an opening to build more equitable societies, but mobilizing those seeking greater equality can contribute to carbon neutrality goals. Webb brought up the example of the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative in Detroit where communities of color are organizing to control their own food supply by bringing climate-resilient and low-carbon agriculture into their neighborhoods. “There are plenty of neighborhoods looking to be completely sustainable, i.e. making sure that people can remain in the neighborhood to meet all of their needs. Creating communities where that is the goal of multiracial residents will be the first step in going carbon neutral.”

Infrastructural inequities and socio-economic inequality are fundamentally intertwined. As Jamie DeAngelo, Decipher City’s other co-founder, told me, “we have to be aware of latent social hierarchies, whether legally enforced or not, and how they persist ghost-like in our spaces.” Communities of color have borne the brunt of environmental injustice—pollution from industrial space, for example—and have been marginalized and policed by a built-in history of racism. Building new decarbonized cities will have to be informed by this history. Removing some traditional fossil fuel-enabled forms of racial control—like huge highways, waste streams, and coal plants—can help do this, but it likely won’t be enough. We have to build both spaces and policies that break down these old racist ghosts that still haunt our cities.

It’s not just about which residents these new or refurbished cities could benefit, or how to make sure we build in equality, but also the more basic question of who gets to move to these cities in the first place. The broader politics that guide climate migrations will ultimately answer that question. The municipal politics within these cities have to be fair, but that’s not enough. Getting national policy right will be absolutely necessary to ensure movement across borders is equitable and humane. Authoritarian capitalist governments will reserve desirable space for the already privileged, leaving the vulnerable to die. A libertarian ecosocialist paradigm, on the other hand, will ensure all get to move and, therefore, live. Any decarbonization plan must incorporate these political values, and construct goals that ensure these political outcomes.

To get a sense of some of the more important areas in which we can build something better, let’s zoom in and imagine what decarbonized, climate-resilient, and equitable cities might look like in more detail. There are three areas in particular that could benefit from reimagining: housing, transport, and entertainment. How can these areas be made better—more equitable, more beautiful—than the cities we know now?

Better Living

Perhaps the one thing every single New Yorker can agree on is that “the rent is too damn high!” Worldwide, city dwellers (except for the “people of means” among us) are united in their discontent at their city’s housing stock. Landlords are universally reviled, for good reason. Housing, maybe more than any other element of a city, illuminates the extreme inequality baked into our society. The rich enjoy sprawling, opulent spaces while everyone else is packed into cramped, unhygienic, ugly ones. But, besides inequality, perhaps the most universal problem with modern housing is its tendency to isolate. Everyone seems pretty lonely. One major reason for this is simply the shape and design of the physical spaces city dwellers inhabit. We live in desolate rooms, inhabited only by ourselves and our stuff.

This doesn’t mean “pack up your stuff, we’re all moving into crowded communes!” Anyone who’s ever shared close quarters with lots of other people knows that it’s usually unbearable and inequitable. There’s always one conscientious person who ends up doing most of the housework (or nobody does, and everything deteriorates). Building mutually supportive social bonds requires that every individual has their own space, a sense of autonomy, and control over their homes. Housing need not be a choice between a commune full of itchy hippies and an isolation box for lonely singles or atomized nuclear families. By disrupting standard models of housing—partly by incorporating food and energy production, such as gardens and solar panels—it’s possible to increase social bonds, give people more control over their space, and build carbon-free, equitable, climate-resilient housing.

Why is it necessary to include gardens and solar panels? Elisa Iturbe, visiting professor at the Cooper Union School of Architecture, explains: “As we move towards a decarbonized future, the integration of energy generation and food production will be essential. From an architectural perspective, these activities could have a spatial presence in the city, which, when paired with alternative land ownership models or cooperative ownership structures, can begin to challenge the norms we have around what constitutes the basic unit of society.” The basic unit here is, of course, the home. When we bring climate-resilient, decarbonized energy capture and agriculture into urban spaces, we can marry these technologies with more pro-social housing that positively impacts how we relate to each other. If we’re working together in the community garden, it may help to cut the epidemic of loneliness we all suffer from in the capitalist city.

Furthermore, renewable energy and onsite food production are also some of the best ways of making housing resilient through a range of climate disasters as solar-powered buildings and agroecological farming in Puerto Rico have demonstrated. If these amenities and spaces are owned cooperatively by the people who live there—as is also seen in the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative—suddenly residents are vastly more empowered by the places they inhabit.

While we’re talking about housing, we have to remember its long history as a tool of racial segregation and economic oppression. In our interview, Professor Iturbe brought up community land trusts and cooperative ownership as means of undermining a real estate market that consolidates property in the hands of a few rich, absent landlords. But other legal and financial aspects of housing—like zoning and mortgage lending—are also riddled with racism. New housing models will have to be governed at a national scale by egalitarian principles if they are to avoid reproducing the inequalities we live with now. The need to build new cities in new places and drastically reform existing cities offers an opportunity to build more racial and economic justice—as well as social bonds—directly into the physical structure of our homes.

Better Moving

Carbon cities are generally terrible at transportation. They were, of course, designed or redesigned for dependency on cars. From a climate standpoint, cars are murderers. Transportation just passed electric power as the primary source of carbon emissions in the US, and this is significantly due to cars.

Car-dependent cities produce bad air quality, incessant noise pollution, and deadly accidents. They turn over abundant space to dangerous, hurtling machines. Even cities with pretty good public transportation still tend to devote tons of space to the needs of large vehicles. As city planner Jeff Speck points out in his book Walkable City Rules, car parking accounts for more acres of space than any other urban use. That means roads bloat, and sidewalks shrink. It also means there are very few spaces to just roam around safely. Freedom of movement gets relegated to parks, which people must crowd into uncomfortably. Anyone who has visited Central Park on a beautiful summer Saturday will understand the feeling of those huge colonies of Adélie penguins packed together against stormy winds in Antarctica. In short, cities designed for cars are good for cars, and bad for people.

In a decarbonized city, there will have to be virtually no fuel vehicles. One could imagine some electric vehicles, but the materials needed to build electric engines and batteries—like cobalt and lithium—are nonrenewable and limited. According to the Guardian, “demand for other key battery ingredients, such as graphite and lithium carbonate, is also outstripping supply. The current shortage of lithium has seen prices double since 2015.” And this is at a time when electric vehicles account for less than 1 percent of market share in the U.S. (Additionally, the rare earth metal extraction process is notoriously dangerous and unethical.) Barring some unforeseen technological breakthrough, we can’t simply exchange every working fossil fuel car for an electric one. What this means for our cities is that we no longer need to build them around big lanes designed for giant metal boxes that routinely kill people. Instead, we can design them around human beings.

Venice has the largest network of pedestrian streets in the world, and it’s, coincidentally, one of the most desirable cities to live in and visit. If you remove cars, you suddenly have a lot more space for people, and can begin filling that space with the objects and activities that people enjoy. Christmas markets with glowing lights and wreaths, the smells of wood smoke and sausages cooking, the taste of hot chocolate or mulled wine while strolling under a dark sky. A big square with a fountain, lined with trees, and dozens of people sitting around under the moon chatting with beers and burgers while a band plays in a pavilion. A narrow cobbled alley with beautiful storefronts and bakeries heavy with the scent of fresh bread. These all can become much more ubiquitous in cities without cars. We know this because, well, they have been in the past.

The Oxford transportation studies professor and top expert in the field, Tim Schwanen, agrees that density, walking, and cycling will have to be important factors in new urban transport. But he also suggests that there are limits to walkability. “Thinking about California and walking and cycling in a 3 degree Celsius increase?” Too hot. And even if we keep the temperature to an unpleasant-but-survivable 1.5 degree increase, people have different needs; some can’t walk far, or at all, and the decarbonized city needs to give them options. Those options will likely need to be a combination of pedal-powered taxi carts and (potentially underground) electric rail or small electric vehicles. But Schwanen cautions against putting too much faith in high-tech solutions. “We have to be careful with technologically utopian visions, we still have to think about the people who will live in the city.”

While cars have been tools of inequality, being prohibitively expensive for precariously employed or poor residents, public transport, too, can suffer from justice issues. It also has been used to segregate and marginalize already disadvantaged populations. Ultimately, when we’re thinking about building better transportation systems, we have to think holistically. Doing so will “require new forms of governance and an overhaul of how transport planning is traditionally done, which is usually very technocratic, top-down, exclusionary, and prioritizes economic growth,” says Schwanen. “We can’t just intervene in transport. It needs to be a full-blown urban policy where justice is prioritized.” With building new cities, this might be less of a problem, but if we’re reforming existing cities, there will be far more obstacles.

Concerted political movements that can, block by block, transform existing cities and build new urban spaces with these principles of justice and equity in mind will be absolutely necessary in designing the next era of urban transit. Transportation planning will also have a huge impact on the rest of the city, as transport is usually the negative space, the weft between buildings, that helps weave together the urban fabric.

Better Fun

Siena, Italy is home to a famous town square, the Piazza del Campo. It’s a big open space in the middle of town resembling a cobblestone piecrust inverted into the ground. Twice per year, a major horserace, the Palio di Siena, takes place in the large, shallow bowl. Year round, the square is ringed with cafes and restaurants, with many outdoor chairs and tables. I visited the Campo one night (pre-smartphone) to find dozens and dozens of people sitting in the square, some with candles and wine, just enjoying the night and each other under a dark Tuscan sky. There are no gates around the square. No velvet ropes, no bouncers, no queues, no ticket to get in. Just open, public space.

In carbon cities, people have fun alone or in privately-owned spaces. Fun is increasingly expensive. Cocktails are $15 minimum in many parts of Brooklyn, and even more across the East River. Brunch, with drinks, can easily exceed $35 per person. A Broadway show or a pop concert can range from $60 a ticket to thousands. Although some cities including New York offer free summer entertainment—like Shakespeare in the Park, or weekly movies projected onto a big screen, or publicly-available barbecue grills—most fun, especially in the winter, takes place in expensive private spaces or in our own cramped apartments, the bare walls splashed with the cool blue light of our laptops.

We can assume in a decarbonized city that we’ll have fewer electrified forms of entertainment, screens or otherwise. But more importantly, building decarbonized cities with ecosocialist principles offers an opportunity to create public spaces that provide free, inclusive, communal sources of fun, particularly if we’re assuming they’re mostly car-free. Preindustrial cities enjoyed vast, beautiful frescoes in elaborate public baths, forums for public debates and theater, lush public gardens (and also, uh, gladiator fights, bear-baiting, and towers of human skulls). In an urban economy that doesn’t put the maximization of profit above all else, we can begin to envision many spaces that are designed for its citizens’ joy (non-sadistic only).

Building Anew

For two years, I’ve had the good fortune to live in the medieval city of Oxford, England. Once burned to the ground by Vikings, the city is now full of beautiful old buildings. It’s basically just beautiful buildings. In the summer, the streets are so clogged with sightseers one has to dodge cars in the streets to get anywhere on time. The city is full of lovely surprises. A winding alley leads mysteriously to a medieval pub. A café with vaulted ceilings attached to a 13th-century church serves the best cheese sandwiches in Britain. There are dozens of old, warmly lit libraries. You may be familiar with the most famous of them: the 18th-century Radcliffe Camera and its iconic dome. This library has appeared in countless television shows and movies. It’s not the only one; on the same square, a different library provided spaces used in some of the Harry Potter movies, just as the city itself has served as a backdrop to countless stories and novels.

But while Oxford is a beautiful spectacle, the mythology of which is owned by the public, the spaces themselves are very exclusive. The Radcliffe Camera is strictly shut to the public at large and even to curious visitors (except for the odd tours and of course, film crews). My delightful college, nestled right next to the Camera, more often than not displays the sign “closed to tourists”. Even as a member of the university, you always feel excluded from something. There’s always some corner that’s off-limits. And Oxford, the City of Dreaming Spires, holds dark secrets, not least of which is the fact that some of these old monuments were built with money from New World slave markets, or that many colleges still invest their funds in arms and fossil fuels. There’s no reason the new cities we build should be any less beautiful than Oxford, any less given to evoking wonder. But there’s also no reason they should be as exclusive, or as dependent on blood.

Recently, the Intercept released an internal video put together by the Pentagon. This video attempts to depict what the world’s megacities—10 million people or larger—will look like in the coming decades and predict how the U.S. military might control them. The image it portrays is, in a word, dystopian. Over melancholy violins, a grim voiceover says, “Cities will be the locus where drivers of instability will converge.” Those “drivers of instability,” says the gritty voiceover guy, include economic inequality, resource constraints, ethnic tensions, and environmental disasters driven by “climate changes.” Networks of violent gangs and terrorists will grow, slums will expand while the rich get richer, and “social structures will be equally challenged if not dysfunctional.” Over images of urban squalor, walled off high-rises, uniformed combat soldiers, and violent police clashes, the voiceover confidently proclaims: “this is the world of our future. […] And it is unavoidable.” If we continue on our current course, governed by homicidal capital, that may be true.

But we don’t have to continue on our current course. If the massive transition before us is governed by a more egalitarian ethic, by ecosocialist principles that put the freedom, health, and well-being of people and the planet above all else, we might finally be able to build a better city, and, with it, a more just civilization. Any Green New Deal—or other all-encompassing policies like it—must incorporate funding and a planning priority to rebuild cities and build new ones with these principles at their core. An ascendant left today is a good sign that these values have a chance at guiding us through this looming transition. But it’s far from guaranteed. Climate emergencies are already fueling the rise of dictators and far-right parties around the world, parties that seek to slaughter the vulnerable and shield the powerful. The left will need to respond by offering a better vision, and prove they have a greater capacity to organize new modes of living in which people can not only survive the impacts to come, but thrive in spite of them. The city is one of the main fronts on which this battle between equitable happiness and brutal misery will continue to rage. For the sake of all those who wish to enjoy lives worth living, it’s a battle we had better win.

This article was originally published in the January – February issue of Current Affairs.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.