It is a place where nobody ever dies, but neither do they have sex. It’s a land of crumbling stately homes, shady garden paths, sleepy villages, country pubs, wood paneled smoking rooms, and well-appointed bachelor flats. It is in England, even when it’s supposed to be America. It’s a gentle place, where the worst that can happen to you is that you fall in a lake while wearing your spats. Breakfast is toast and marmalade, perhaps with an egg, plus a strong pot of tea. Everyone is at least comfortably well-off, though inexplicably nobody ever seems to have any cash on hand—leading to constant fretting and attempts to borrow a tenner to put on a horse. People get into scrapes, perhaps involving the purloining of a ghastly antique, or the impersonation of an earl, or an attempt to thwart an undesirable engagement.

Nothing in this world ever changes.

P.G. Wodehouse wrote about 90 books in his lifetime, and it’s likely that he would have continued to crank them out indefinitely if he hadn’t finally died at age 95. He is, to those who love him, the finest writer of comic prose in English. His more cultish devotees call him “The Master.” But his work is also defiantly “old-fashioned,” repetitive, and frivolous. It contains no biting satire, no real depth of feeling. It is the most gentle sort of humor imaginable, free of even the lightest innuendo. How to convey, then, the peculiar joy that comes with entering the World of Wodehouse?

The first point to make in his favor is that Wodehouse had a spectacular, possibly unequaled, talent for writing interesting sentences. It is hard for a writer to be truly original, to avoid drawing from the common stock of prefabricated cliches. But a page of Wodehouse overflows with original and memorable phrases. Bizarre similes, for instance, are littered casually throughout his stories. A few selections:

- “The Duke puffed at his moustache approvingly, so that it flew before him like a banner.”

- “She looked at me like someone who has just solved the crossword puzzle with a shrewd ‘Emu’ in the top right-hand corner.”

- “He looked as if he had been poured into his clothes and forgotten to say ‘when.’”

- Upon touching a cold slice of tongue in the dark: “To say that Baxter’s heart stood still would be medically inexact. The heart does not stand still. Whatever the emotions of its owner, it goes on beating. It would be more accurate to say that Baxter felt like a man taking his first ride in an express elevator who has outstripped his vital organs by several floors and sees no immediate prospect of their ever catching up with him. There was a great cold void where the more intimate parts of his body should have been.”

- “Of Mrs Twemlow little need be attempted in the way of pen-portraiture beyond the statement that she went as harmoniously with Mr Beach as one of a pair of vases or one of a brace of pheasants goes with its fellow. She had the same appearance of imminent apoplexy, the same air of belonging to some dignified and haughty branch of the vegetable kingdom.”

People who love Wodehouse love him in part because no other author would think to introduce a character thusly:“[T]here entered a young man of great height but lacking the width of shoulder and ruggedness of limb which make height impressive. Nature, stretching Horace Davenport out, had forgotten to stretch him sideways, and one could have pictured Euclid, had they met, nudging a friend and saying, ‘Don’t look now, but this chap coming along illustrates exactly what I was telling you about a straight line having length without breadth.’”

The old hackneyed phrases are constantly played with and inverted. Of an unsavory character, Wodehouse writes: “He was grim and resolute, his supply of the milk of human kindness plainly short by several gallons.” Jeeves, the omniscient valet, does not come and go from rooms, but instead shimmers, materializes, floats, drifts, or trickles. Strunk and White’s famous dictum, “Never use a long word when a short one will do” does not apply, instead Wodehouse’s rule seems to be “Never use the standard expression for something if you can think of something more vivid.” An old man is a “whiskered ancient.” A problem didn’t “eat at him,” it “gnawed the vitals.” Or the unique coinages: “I have been in some tough spots in my time, but this one wins the mottled oyster.” Who on earth says this?? And who but Wodehouse would title one chapter in a book “Almost Entirely About Flower-Pots” and follow it immediately with one entitled “More On The Flower-Pot Theme”?

Most of Wodehouse’s best-known novels are set in a bucolic Britain of country houses and castles. They have terraces, smoking rooms, libraries, and smoothly-shaved lawns. There is an atmosphere of leisured cosiness: of scrumptious cake, summer flowers, and perfectly-mixed cocktails. There’s a heavy dose of The Importance of Being Earnest and The Pickwick Papers, and the amount of Englishness per paragraph can be downright sickening. Classic English understatement is also taken to extremes: when being threatened by a fascist, Bertie Wooster observes: “One sensed the absence of the bonhomous note.”

The characters are usually well-to-do, asset-rich but cash-poor. Many are dilettantish young aristocrats, to which Wodehouse has a particular gift for assigning silly but somehow plausible names (Gussie Fink-Nottle, Monty Bodkin, Pongo Twistleton, Freddie Threepwood, Catsmeat Potter-Pirbright, Bingo Little, Barmy Fotheringay-Phipps). Everyone went to Oxbridge and Eton. They are all stupid, or at least a little daft. Most have a network of aunts and uncles who cause havoc. Occasional Americans show up, exclaiming things like “Gum!” and “Shucks!” at the start of every sentence. (Wodehouse, though he spent much of his life in the United States, and seems to have preferred it to England, never had quite the same ear for American speech.) Servants, usually more intelligent than their employers, flit about. Industrialists, detectives, nerve specialists, and impostors disguised as poets infiltrate country homes and engage in elaborate underhanded schemes.

Then there are Wodehouse’s plots. A Wodehouse plot is a thing of awesome intricacy and absurdity, like a cuckoo-clock of many interlocking gears, deploying dozens of spring-loaded, squawking birds. As the novel unfolds, the story becomes steadily more and more convoluted, with mishaps, double-crossings, mistaken identities, thefts, broken engagements, and occasional slapstick violence. The storylines build to a steady crescendo, converge on one another, and then neatly resolve themselves in the final chapters. Here is a representative synopsis:

The Honorable Galahad Threepwood has changed his mind and decided not to publish his scandalous memoir with Lord Tilbury’s publishing house. Galahad’s nephew Ronnie is set to marry Sue Brown, the daughter of Galahad’s old flame, but the marriage is controversial in the family because Sue is a chorus girl. Galahad’s sisters, Lady Constance and Lady Julia, agree to approve the marriage if Galahad declines to publish the memoir, which is full of embarrassing facts about members of the peerage. Meanwhile, Lord Emsworth is convinced that Sir Gregory Parsloe is trying to steal his prize pig. Monty Bodkin, Sir Gregory’s nephew, has been freshly fired from Lord Tilbury’s publishing house and takes a job as Lord Emsworth’s secretary. But Monty Bodkin and Sue Brown were once engaged, and Sue worries that Ronnie will be jealous when Monty comes to the castle. Monty and Sue agree over lunch that they will pretend to be strangers. When Ronnie meets his Aunt Julia, she forbids the marriage, believing Sue to have betrayed Ronnie by pretending not to know Monty. Meanwhile, Lord Tilbury schemes to steal Galahad’s manuscript and publish it. Further complications ensue.

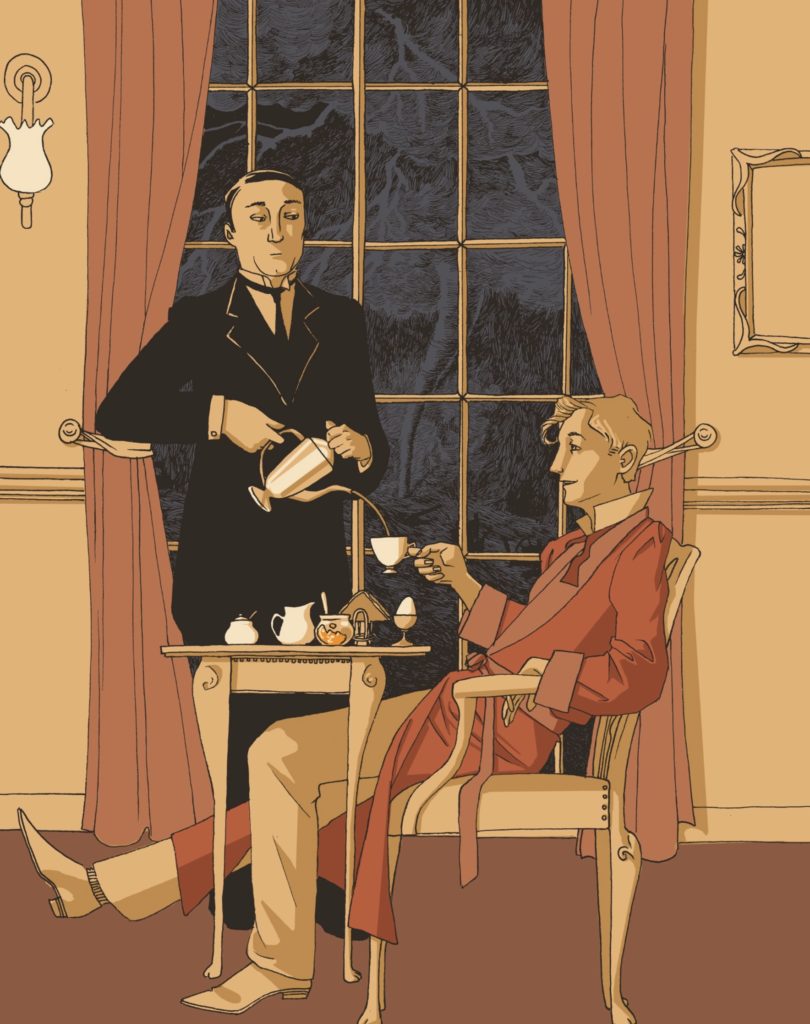

Wodehouse is today best known for his Jeeves and Wooster stories, concerning the activities of wealthy man-about-town Bertie Wooster and his genius valet, Jeeves. (Jeeves and Wooster were memorably portrayed on BBC television by Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie, although the densely-packed humor of Wodehouse’s prose only translates incompletely to the screen.) A typical Jeeves story features Bertie doing something of which Jeeves disapproves, such as growing a mustache, or buying a pair of purple socks. Bertie then finds himself—partly through Jeeves’ behind-the-scenes machinations, partly through Bertie’s own quasi-religious adherence to the preux chevalier “Code of the Woosters,” which requires him to assist any friend in need, no matter how absurd their demands—in the midst of a “scrape,” usually requiring him to impersonate an important personage, conceal a stolen object, or facilitate a forbidden love-affair. When everything has gone awry and all hope seems lost, Jeeves then swoops in and uses his powerful, “fish-fed” brain to extricate Bertie from his predicament. Bertie, out of gratitude, then agrees to relinquish whatever sartorial outrage caused their initial rift.

But our own favorite Wodehousean creation is a character that, tragically, did not spawn nearly as many sequel novels or television adaptations. He is the delightful, demented dandy known as Psmith.

Enter Psmith

Although it is not entirely clear if his first name is Ronald or Rupert, we know that his last name is “Psmith”—and that “the ‘p’ is silent, as in ‘pshrimp.’” Tall, thin, and solemn, Psmith is immaculately dressed at all times, wears a monocle, and sleeps in late because “a German doctor says that early rising causes insanity.” He is constantly falling afoul of his family’s expectations, first by failing out of Eton, and then by abandoning his uncle’s fish business. We variously encounter Psmith working in extremely desultory fashion at the New Asiatic Bank; muscling his way into the subeditorship of a provincial magazine called Cozy Moments (which he subsequently remakes as a muckracking, tenement-busting radical paper); and freelancing under the following expansive advertisement:

LEAVE IT TO PSMITH!

Psmith Will Help You

Psmith Is Ready For Anything

DO YOU WANT

Someone To Manage Your Affairs?

Someone To Handle Your Business?

Someone To Take Your Dog For A Run?

Someone To Assassinate Your Aunt?

PSMITH WILL DO IT

CRIME NOT OBJECTED TO

Whatever Job You Have To Offer.

(Provided It Has Nothing To Do With Fish.)

Psmith self-identifies as a Socialist and states that “socialism is the passion of my life,” though his praxis amounts to calling everybody “comrade” and casually redistributing the odd bit of property, e.g. by stealing another man’s umbrella and giving it to a pretty girl in a rainstorm. (In Psmith’s defense, these are basically the foundations of the doctrine.) Psmith, nonetheless, is the closest thing to a socially-conscious character that exists in the World of Wodehouse. In an uncharacteristically serious chapter of Psmith, Journalist, he stumbles across a tenement-sweatshop in a New York slum and declares:

“I propose… to make things as warm for the owner of this place as I jolly well know how. What he wants, of course,” he proceeded in the tone of a family doctor prescribing for a patient, “is disembowelling. I fancy, however, that a mawkishly sentimental legislature will prevent our performing that national service.”

As a general rule, however, Psmith is much less bloodthirsty. His personal mission in life is the “spreading of sweetness and light.” His friend Mike notes Psmith’s “fondness for getting into atmospheres that were not his own” and his gift for “getting into [other people’s] minds and seeing things from their point of view.” He moves through the world with unflappable self-confidence, and comfort in his own peculiar skin. “Reflect that I may be an acquired taste,” he remarks to his companion. “You probably did not like olives the first time you tasted them. Now you probably do. Give me the same chance you would an olive.” In the one novel where Psmith is paired with a love-interest, he also reveals himself to have an unerring instinct for what human beings look for in romantic partners:

“By the way, returning to the subject we were discussing last night, I forgot to mention, when asking you to marry me, that I can do card-tricks.”

“Really?”

“And also a passable imitation of a cat calling to her young. Has this no weight with you? Think! These things come in very handy in the long winter evenings.”

“But I shan’t be there when you are imitating cats in the long winter evenings.”

“I think you are wrong. As I visualize my little home, I can see you there very clearly, sitting before the fire. Your maid has put you into something loose. The light of the flickering flames reflects itself in your lovely eyes. You are pleasantly tired after an afternoon’s shopping, but not so tired as to be unable to select a card—any card—from the pack which I offer…”

“Good-bye,” said Eve.

Although Psmith’s unusual behavior regularly astonishes those around him, Psmith himself is never surprised by anything, no matter how odd. His motto in life, he states, is “never confuse the improbable with the impossible.” He is always running several grifts simultaneously, usually for the combined goals of discomfiting bores and bullies, helping the underdog, and amusing himself. No setback ever deters him. “Nothing that you can say can damp my buoyant spirit,” he declares. “The cry goes round the castle battlements: ‘Psmith intends to keep the old flag flying!’”

Politics and Wodehouse

The qualities of his output aside, if there was a contest for “most naïve man of the 20th century,” P.G. Wodehouse would be a favorite to take the cup. Though he was writing during some of the bloodiest upheavals in human history, Wodehouse seems to have been passed by almost completely by world events. Even in the 1960s novels, Bertie Wooster is still living as if it’s 1923, and World Wars One and Two barely cross the page. In fact, George Orwell says that the imaginative landscape of the books was set even earlier, that it’s pre-WWI, since by the 20s the types of characters Wodehouse was writing about had been massacred by the hundreds of thousands. Bertie Wooster and Gussie Fink-Nottle, had they existed, would have ended their lives being eaten by rats in the trenches of Flanders. As it is, we’re to believe that Wodehouse’s dandies either never went to war, or, if they did, that it made no impression on them whatsoever. “If ever my grandchildren cluster about my knee and want to know what I did in the Great War,” Bertie Wooster states in Jeeves and the Song of Songs, “I shall say: ‘Never mind about the Great War. Ask me about the time I sang “Sonny Boy” at the Oddfellows’ Hall at Bermondsey East.’”

There are certain passing references to political and social ideas that Wodehouse seems to have picked up by glancing at newspaper headlines. A character may make a passing reference to “what with all this Socialism rampant.” In The Clicking of Cuthbert, a visiting Russian novelist remarks that “you know that is our great national sport, trying to assassinate Lenin with rewolwers.” Wodehouse seems to have known who at least some world-historic figures were, saying of one character that “when it came to self-confidence, Mussolini could have taken his correspondence course.” In The Code of The Woosters, Wodehouse creates one of his most fearsome villains, Sir Roderick Spode, a fascist in the mold of Sir Oswald Moseley. Spode leads a gang of right-wing thugs called the Black Shorts (by the time they formed, there were no more shirts left). While it’s clear that Wodehouse sees Spode as a nasty bugger, he also seems to have thought of fascists simply as laughable pompous goose-steppers, and doesn’t exactly grasp the stakes. (Spode’s menace ultimately proves easy to neutralize, as it turns out that he secretly runs a woman’s lingerie business and is terrified that word will get out.)

The most political Wodehouse’s fiction gets is in a short story called “Archibald and the Masses,” in which a young aristocrat decides to flirt with Socialism, but pisses off every proletarian he meets and tries to help, finally concluding that the Masses are not his cup of tea. Here, at the outset, his valet offers to introduce him to the doctrine:

“You should go down to a place like Bottleton East. That is where you hear the Voice of the People.”

“What people?”

“The masses, sir. The martyred proletariat. If you are interested in the martyred proletariat, I could supply you with some well-written pamphlets. I have been a member of the League for the Dawn of Freedom for many years, sir. Our object, as the name implies, is to hasten the coming revolution.”

“Like in Russia, do you mean?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Massacres and all that?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now listen, Meadowes,” said Archibald firmly. “Fun’s fun, but no rot about stabbing me with a dripping knife. I won’t have it, do you understand?”

“Very good, sir.”

“That being clear, you may bring me those pamphlets. I’d like to have a look at them.”

It’s not exactly a pro- or anti-Socialist message. There are no “morals” in these silly stories, no real stances taken. Socialism is funny because everything is funny. That also means, though, that Wodehouse isn’t really attempting “satire” on English upper class life. Even though he pokes fun at their names, their indolence, their frippery, ultimately he is no class warrior. Butlers and valets are important characters in the stories, but only if you squint closely do you notice that the entire social milieu is being sustained by a vast army of housemaids, lady’s maids, scullery-maids, footmen, chauffeurs, under-butlers, governesses, nursery-maids, pantry-boys, hall boys, laundry-maids, chefs, secretaries, gardeners, groomsmen, and groundskeepers. (And these are just the direct servants. If we peered into a British factory of the time, we’d see the real underbelly.) The class system isn’t hidden, exactly—it’s the source of many of the stories’ conflicts, with characters judged by relatives for marrying outside their station. But we certainly see none of the actual labor—and as Orwell put it, one of Wodehouse’s chief sins is that he made the British upper classes seem like much nicer people than they actually are.

Wodehouse, a workaholic with an uneventful personal life, paid scant attention to anything going on around him. Mentally, he seems to have actually inhabited the cheery, detached world of his books: he privately described himself in a letter to a friend as “a case of infantilism… I haven’t developed mentally at all since my last year at school.” He was not exaggerating. And that childlike disposition might seem somewhat forgivable and endearing, had it not led to the most infamous incident of Wodehouse’s life: bumbling his way into collaborating with the Nazis.

At the time, it caused an uproar in Britain, and it permanently damaged Wodehouse’s reputation. The facts are these: in 1941, Wodehouse was living in a seaside villa in Le Touquet, France—evidently for tax-evasion purposes. He seems to have ignored the existence of World War II entirely, and was completely taken by surprise when the Nazis invaded. He was placed in an internment camp, where he was relatively well-treated. He was then approached by the Third Reich’s propaganda ministry, who asked him if he would do a series of radio broadcasts describing his time in the camp. Wodehouse not only obliged, but actually accepted payment for his addresses.

The broadcasts were not pro-Nazi. They were typical Wodehouse—light, affable, apolitical. Wodehouse seems to have approached the decision to do the broadcasts with characteristic dreaminess. Say, these jackbooted chaps have asked me to do a bit of radio. No harm saying a few words, eh? A representative excerpt:

“Wodehouse, old sport, I said to myself, this begins to look like a sticky day. And a few moments later my apprehensions were fulfilled. Arriving at the Kommandantur, I found everything in a state of bustle and excitement. I said “Es ist schönes wetter” once or twice, but nobody took any notice. And presently the interpreter stepped forward and announced that we were all going to be interned. It was a pretty nasty shock, coming without warning out of a blue sky like that, and it is not too much to say that for an instant the old maestro shook like a badly set blancmange. … Having closed the suitcase and said goodbye to my wife and the junior dog, and foiled the attempt of the senior dog to muscle into the car and accompany me into captivity, I returned to the Kommandantur. And presently, with the rest of the gang, numbering twelve in all, I drove in a motor omnibus for an unknown destination. … An internee’s enjoyment of such a journey depends very largely on the mental attitude of the sergeant in charge. Ours turned out to be a genial soul, who gave us cigarettes and let us get off and buy red wine at all stops, infusing the whole thing with the pleasant atmosphere of a school treat.”

George Orwell, in his essay “In Defense Of P.G. Wodehouse,” concludes that Wodehouse was just unfathomably stupid and does not seem to have understood what a Nazi even was. He would never have deliberately betrayed England—after all, that “wouldn’t be cricket,” and Wodehouse lived by the public schoolboy code of honor. But he doesn’t seem to have had the slightest suspicion that Hitler might be using him for nefarious purposes. Indeed, Wodehouse was so clueless that his exasperated friends had to persuade him out of writing a humorous memoir about his internment several years later. In one of the draft chapters that survives, Wodehouse described his ongoing bafflement at the public reaction to his decision to participate in the broadcasts: “the global howl that went up as a result of my indiscretion exceeded in volume and intensity anything I have ever experienced since that time in my boyhood when I broke the curate’s umbrella and my aunts started writing letters to one another about it.”

The fact that someone could “oops a daisy” his way into serving the Reich tells us something important about the limitations of his worldview. If politics don’t intrude on life in the Wodehouse snowglobe, they certainly do on most people’s lives. To neglect to peer out of one’s own bubble of privilege and comfort is a profound moral failing.

‘The tie, if I might suggest it, sir, a shade more tightly knotted. One aims at the perfect butterfly effect. If you will permit me— ’

‘What do ties matter, Jeeves, at a time like this? Do you realize that Mr Little’s domestic happiness is hanging in the scale?’

‘There is no time, sir, at which ties do not matter.’

One either eats this stuff up or one does not. We do.

Why enter this world? A place with so little drama, so much golf? Because it overflows with loveliness and good cheer, for one thing. It will brighten your day and transport you to a land with fewer problems than this one. It will expose you to some of the warmest and most creative prose in the English language.

But like all utopias, the World of Wodehouse has a dark side. You can’t actually be like P.G. Wodehouse, because that would mean overlooking criminal injustices. Wodehouse’s own life showed what happens if one becomes too much the absent-minded bumbler. To bumble in a country garden is charming. To bumble amidst a Holocaust is sickening. There are times that call for moral clarity and courage. We have to remember that the real Bertie Woosters did not live in their idyll forever, as they do in the pages of the Jeeves stories. They died horribly in a catastrophic war. Wodehouse’s work shows how delightful the world can be, but it overlooks the suffering in the midst of that delight, and the suffering of the many that has always enabled the delight of the few. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying it. The stories are hilarious, they’re sweet, they’re gorgeously written. But one can’t inhabit a snowglobe.

We might even take a lesson from Psmith here, who despite his serene, careless gaiety, is genuinely concerned with the welfare of his fellow-creatures, even if he expresses it in unusual ways. (Such as, for instance, by hurling a flowerpot through an open window into a library.) We must spread sweetness and light, and we must always keep the old flag flying.