Nearly every human society has figured out how to get high. This behavior isn’t limited to Homo Sapiens—a number of animals also do recreational drugs. So why do we and some of our finned and hoofed brethren seek to escape normal consciousness? Well, as an active participant in normal consciousness, I don’t find the mystery too great: normal consciousness often sucks. Our brains are powerful problem-solving machines that evolved to protect and pass along our genes. In many situations, achieving that goal is unrelated to being happy.

“The mental healthcare system is so badly broken, it doesn’t even qualify as a system.” This indictment, coming from Tom Insel, the former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, is not due to lack of effort. The U.S. spends over $200 billion on mental healthcare treatment each year, double what we spent in 2005. American suicides are at a fifty year high and increasing at an increasing rate. Over 70,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2017, twice as many as did in 2007.

Our best responses to depression, addiction, and PTSD haven’t changed much. SSRI’s, introduced in the 1980s, work only with some forms of depression, have not improved, and carry side-effects that their users hate. Only 8 to 12 percent of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) members get sober after the first year, and the organization has resisted the introduction of more effective drug-based treatments. Talk-based therapy is expensive, time-consuming, and often ineffective.

Rather than throw up their hands in the face of maladies that are affecting tens of millions of Americans and hundreds of millions more worldwide, researchers are turning back to a class of compounds that have were exiled from the medical establishment over 40 years ago.

Classical psychedelics were administered to over 10,000 people in research settings in the 1950s and ’60s. Acting primarily on the 5HT2A subtype of serotonin receptors and sharing a similar chemical structure, classical psychedelics are generally thought of as psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms), LSD, mescaline, and DMT. MDMA (i.e. Molly or Ecstasy) shares some features, but is neurotoxic at high doses and can lead to dependencies not seen in the classical psychedelics. Classical psychedelics share more than just structure and method of action, they are anti-addictive (they help users break addictions and don’t create dependencies themselves), non-toxic, and generally affect the mind far more than they affect the body. (Someone tripping on a high dose of LSD will exhibit normal vital signs, and the only external evidence of the experience is pupil dilation).

At low to medium doses, psychedelics can induce a dreamlike state: imagination is heightened, time may feel as if it is passing slower than usual, and visuals distort, creating the appearance of movement where there is none (“the walls are breathing”). Psychedelics can intensify positive emotional states, particularly feelings of awe, wonder, and bliss, and increase feelings of trust and empathy. They can also intensify negative emotions, especially paranoia and feelings of losing control. But a summary of the research on the psychedelic experience has found that “…the majority of emotional psychedelic effects in supportive contexts are experienced as positive.” At higher doses (sometimes called “entheogenic” doses for their ability to create spiritual experiences), psychedelics can break down the barrier between self and the external world. Some users experience “ego death”, the “complete loss of subjective self-identity”. Insights gained during periods of ego death can take on the quality of objective truth, which helps explain the power of psychedelics to inspire sustained behavioral changes (as well as some of the more peculiar beliefs about the universe some psychedelic users take away from the experience). Reports of mystical experiences brought on by high doses of psychedelics appear similar to reports of non-drug related mystical experiences: an overwhelming sense of unity with the cosmos, transcendence of space and time, ineffability, and what William James called “the Noetic Quality”: the deep feeling that what is learned during the experience is capital T True.

Recent psychedelic research has demonstrated the ability of psychedelics to beat our current best treatments for depression, addiction, PTSD, smoking, alcoholism, and existential anxiety. A lot of these studies are conducted by highly-motivated researchers on small samples and may not generalize. But the promise of psychedelics across such a wide range of ailments may indicate that mental illnesses aren’t as varied as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders would have us believe. The ability of psychedelics to help people with treatment-resistant mental illness (those that persist after two or more forms of treatment have been attempted) may foreshadow even better results in populations with less severe conditions. David Nutt, Britain’s former director of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, told me over email that these results are “almost certain” to generalize.

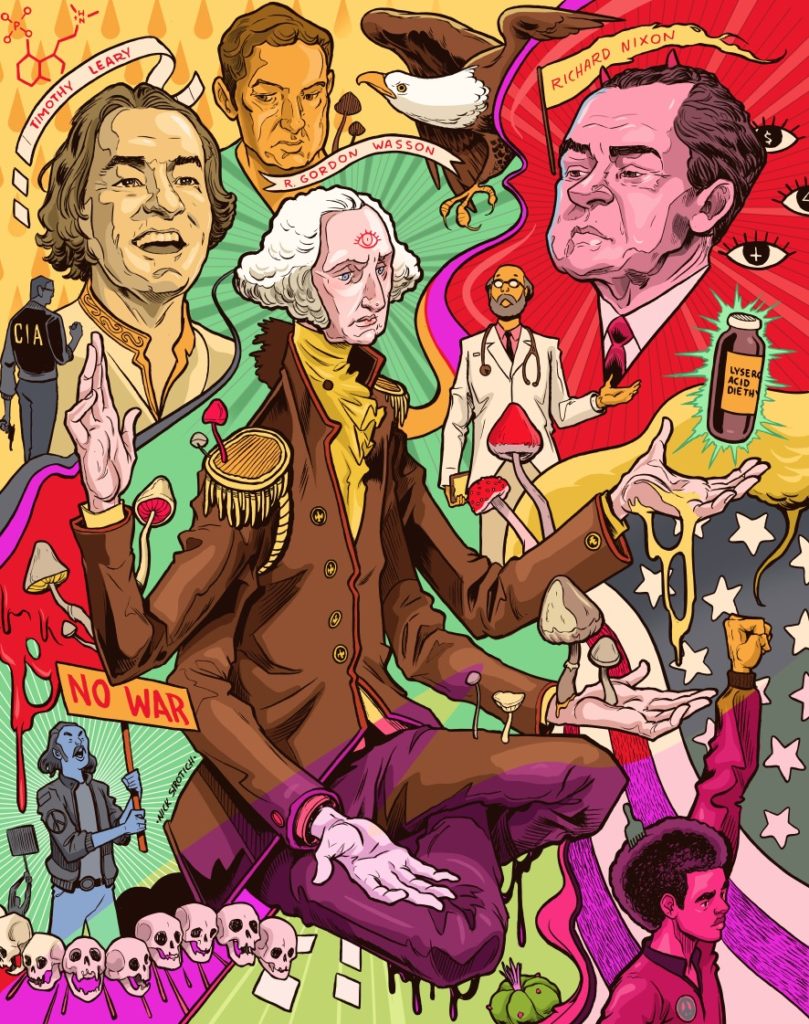

While psychedelics have been used by human societies for thousands of years, they weren’t widely introduced to the U.S. until 1957, when R. Gordon Wasson detailed his magic mushroom experience with a Shaman in Mexico in Life Magazine. Albert Hoffman stumbled upon the psychoactive properties of his creation lysergic acid diethylamide-25 (LSD) fourteen years earlier. Hoffman’s firm, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, had already been sending LSD to therapists for nearly a decade.

From the 1940s to the early 1960s, psychedelics were seen as a wonder drug, embraced by respected and mainstream celebrities like Cary Grant, Jack Nicholson, Stanley Kubrick, and Aldous Huxley (whose 1954 book The Doors of Perception describing his experience with mescaline did its share to pique interest in psychedelics among the Western upper crust). Researchers couldn’t believe how effective these drugs were. A 1967 article reviewing 42 papers studying psychedelics therapy conducted between 1953 and 1965 found therapy to be successful in 70 percent of anxiety cases, 62 percent of depression cases, and 42 percent of OCD cases. However it should be noted that these studies were largely uncontrolled (publication standards have increased since the 1950s and 1960s).

After showing so much promise as a therapeutic tool and revealing deep truths about the mind (the discovery of LSD’s similarity to serotonin arguably kicked off modern neuroscience), LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline are Schedule I drugs: they have high potential for abuse and no accepted medical uses. Research significantly dropped off in 1966 and froze in 1976.

What happened?

Psychedelic History

Nixon declared the start of the “War on Drugs” in 1971, but the first shots were fired far earlier. The United States has a long history of criminalizing drugs associated with social undesirables, detailed in Johann Hari’s book Chasing the Scream. Premonitions of the war to come can be found in late 19th century. Fears of Chinese immigrants using opium to seduce white women contributed to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. A 1914 New York Times headline informed their readers that “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends’ Are a New Southern Menace.” This climate led to the passage of the Harrison Act the same year, which effectively criminalized cocaine and heroin.

Harry Anslinger, the fanatical and viciously racist founder of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, is the founding father of the drug war. In the 1920s, Anslinger prosecuted 35,000 doctors for prescribing controlled drugs to addicts, overriding a Supreme Court decision (this would not be the first time drug enforcers ignored judicial opinion) and ceding control of addictive drugs to the black market. After successfully pushing for marijuana criminalization in 1937, Anslinger took his show on the road. Invoking fears of Chinese “Communist heroin”, he threatened to cut other countries off from American foreign aid and markets if they didn’t adopt drug laws similar to America’s. In the words of a retired DEA agent, “He was truly the founder of international drug enforcement.”

There is a tendency to see the backlash to psychedelics as an avoidable tragedy brought on by the “antics” of Timothy Leary and other evangelizers. While psychedelics may have seemed poised to become a part of the mainstream, the infrastructure to criminalize substances in the face of all evidence was built long before Leary emerged on the scene.

The history of the psychedelic 1960s is well-documented in Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain’s Acid Dreams: the Complete Social History of LSD. The media narrative went something like this: an extremely promising drug (LSD) was being used responsibly and to great effect by pioneering therapists and intellectuals. Along come reckless scientists like Timothy Leary and counter-culture populists like Ken Kesey, who heave psychedelics over the wall separating the educated classes from the great unwashed. In response to the social and public health crisis that resulted from millions of people turning on, tuning in, and dropping out the government steps in, first when the FDA regulated acid as an experimental drug in 1962, then when California banned it in 1966, with the final nail coming with the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, which inaugurated the modern war on drugs.

A different story played out beneath the surface. Inspired by the use of mescaline on prisoners in Dachau, the CIA became keenly interested in drugs, as truth serums, biological weapons, and methods of mind-control. This highly secret program was known by the codename MK-ULTRA. After extensive experimentation, the Agency settled on LSD. Effective in micrograms (one millionth of a gram), odorless, colorless, and tasteless, acid was well-suited for covert operations. However, the effect of the drug was so unpredictable that the CIA struggled to determine its best use. LSD could be used to subvert psychological defenses during interrogations, but it could just as easily provoke nonsensical answers. For this reason, they believed it could be used defensively like a suicide pill, allowing a captured agent a temporary escape hatch from reality. But what if we weren’t the only ones who were pharmacologically curious? What if the Russians dosed an American city’s water supply?

These questions needed answers, and the CIA was willing to pay for them. Before the Agency took an interest, few American scientists were researching LSD, as Lee and Shlain write, “Almost overnight a whole new market for grants in LSD research sprang into existence as money started pouring through CIA-linked conduits or ‘cutouts’ such as the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research, the Society for the Study of Human Ecology, and the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.” R. Gordon Wasson’s expedition to find the magic mushroom- the event that truly kicked off American psychedelia- was funded by MK-ULTRA.

This research was conducted from the perspective that LSD could induce a temporary or “model” psychosis in the laboratory. This thesis claimed that acid was a “psychotomimetic” or “madness-mimicking” substance. By creating an experience like schizophrenia in a controlled setting, scientists hoped to understand and ultimately cure the illness. Dosed unwittingly, or while strapped to a chair in a windowless lab, people often responded as if they were losing their minds, confirming the psychotomimetic thesis in the eyes of their observers.

The CIA engaged in research of their own, surreptitiously drugging each other along with hundreds of civilians, lured into brothels cum laboratories run by agent George White. Numerous participants in these non-consensual experiments became ill, and “some required hospitalization for days or weeks at a time.” Experiments on non-consenting civilians violate the Nuremberg Code, but none of the people responsible were held accountable. In a letter to Sidney Gottlieb, MK-ULTRA’s director, White wrote of his experience, “…it was fun, fun, fun. Where else could a red-blooded American boy lie, kill, cheat, steal, rape, and pillage with the sanction and blessing of the All-Highest?”

By the time the FDA took an interest in LSD in 1962, the CIA had supported enough basic research and shifted their focus to applied:

“They had given up on the notion that LSD was ‘the secret that was going to unlock the universe.’ While acid was still an important part of the cloak-and-dagger arsenal, by this time the CIA and the army had developed a series of superhallucinogens such as the highly touted BZ, which was thought to hold greater promise as a mind control weapon.”

The FDA regulations, however, had an exemption for any studies the military or CIA wanted to conduct, “Apparently, in the eyes of the FDA, those seeking to develop hallucinogens as weapons were somehow more ‘sensitive to their scientific integrity and moral and ethical responsibilities’ than independent researchers dedicated to exploring the therapeutic potential of LSD.”

Further restrictions on research followed, and bad publicity forced Sandoz to stop marketing LSD entirely in April 1966. Two years later, acid possession was criminalized and the FDA relinquished its authority over the drug to the newly formed Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, an amalgamation of Anslinger’s agency and the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control. These restrictions, of course, did not apply to the military or CIA. An official in the FDA’s parent department admitted that “we are abdicating our statutory responsibilities in this area out of a desire to be courteous to the Department of Defense. . . rather than out of legal inability to handle classified materials.”

Historically, the U.S. criminalized drugs when they became associated with poor people and people of color. Psychedelics, however, were favored by well-educated, white, middle-class youth. Octavio Paz, a writer in an alternative publication, (correctly) identified the real motivation at the time:

“The authorities do not behave as though they were trying to stamp out a harmful vice, but as though they were attempting to stamp out dissidence. Since this is a form of dissidence that is becoming more widespread, the prohibition takes on the proportion of a campaign against a spiritual contagion, against an opinion. What the authorities are displaying is ideological zeal: they are punishing a heresy, not a crime.”

Years later, we got confirmation of the cynical roots of the 1960s incarnation of the war on drugs, as Richard Nixon’s Domestic Policy Advisor, John Ehrlichman explained in 1994:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people…We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

In 1975, The Rockefeller Commission investigated the CIA and summarized the Agency’s objective with MK-ULTRA: “Can we get control of an individual to the point where he will do our bidding against his will and even against fundamental laws of nature, such as self-preservation?” Two years later psychologist Bill Richards administered the last legal psilocybin session in the United States, until the recent resurgence of research.

But the psychoactive baton was passed to a new wonder drug: MDMA. Also known as ecstasy or molly, MDMA was ignored after it was first synthesized in 1912 by Merck, at least until psychedelic chemist Sasha Shulgin popularized the drug in the 1970s.

MDMA followed a similar path to its cousin, LSD. Initially hailed as a therapeutic wonder drug, it became associated with the rave scene in the 1980s and was subsequently criminalized, despite the protestation of scientists who were aware of its potential to help people and the ruling of an administrative judge to place MDMA in Schedule III.

Out of the eyes of the mainstream press and public, psychedelics continued to be employed by underground guides in therapeutic and spiritual contexts. They also played a role in shaping the rise of modern festival culture. Burning Man, the dionysian weeklong experimental society that emerges in the Nevada desert each year, is built by and for people on psychedelics. Inheriting the Merry Prankster ethos of participatory anarchy, Burning Man is the closest example to what an psychedelic American society could be: insanely creative, open-minded, community-oriented, and just a tad detached from reality.

A group of true believers never gave up on the promise of psychedelics and can largely be credited with the renaissance underway. Rick Doblin founded the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) in 1986, the year after MDMA was criminalized. MAPS is the most prominent organization pushing for political change on psychedelics and has funded the research on MDMA for PTSD, which is beginning phase three clinical trials with the FDA. Should these trials succeed, MDMA will be moved from schedule I to schedule III in 2021, the equivalent of going from being treated like heroin to being treated like low-dose Codeine.

Purdue University pharmacologist David Nichols founded the Heffter Institute in 1993. Named after the German chemist who first isolated mescaline from the peyote cactus, Heffter funded research on treating anxiety in cancer patients and alcohol and smoking addiction. Nichols also synthesized the MDMA and psilocybin used in recent research.

The same year Heffter was founded, Bob Jesse founded the Council on Spiritual Practices (CSP). “Dedicated to making direct experience of the sacred more available to more people”, CSP organized and funded the first psychedelic experiments at Johns Hopkins and supported the suit that led to the Supreme Court’s decision in 2006 to recognize ayahuasca as a sacrament in the UDV Church.

These groups and the scientists they support have tirelessly worked to rehabilitate the scientific and social reputation of psychedelics. In the face of onerous and anti-scientific restrictions from the government, they are beginning to succeed- but the fight is far from over. It is just now that we are beginning to step out of Harry Anslinger’s long shadow.

Psychedelic Capitalism

Psychedelics don’t quite fit within the capitalist framework. People enjoy doing them enough to pay for the pleasure, but the black market for psychedelics is small (classical psychedelics aren’t even discussed in the DEA’s 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment). Mushrooms sell for around $10 per gram on the black market, coming out to roughly $35 per trip. Drug dealers are subject to the same market pressures as “legitimate” capitalists. Are they going to choose to carry anti-addictive drugs that people typically buy in small quantities, or cocaine?

LSD’s patent in the U.S. was granted in 1948 and expired in 1965. Not sure what to do with their accidental discovery, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals sent acid out for free and in return scientists and therapists shared their research. By the time other pharmaceutical companies were allowed to manufacture their own LSD, the government and media had turned on the compound. Sandoz recalled the drug from researchers in 1966, the same year it became illegal in California. The black market stepped in to meet the demand that had been stoked by evangelizers like author Ken Kesey. But these were no ordinary drug dealers. Legendary underground chemists like Augustus Owsley and Tim Scully manufactured millions of hits of acid. Quoted in Acid Dreams, Scully was motivated by more than just the bottom line:

“Every time we’d make another batch and release it on the street something beautiful would flower, and of course we believed it was all because of what we were doing. We believed that we were the architects of social change, that our mission was to change the world substantially, and what was going on in the Haight was a sort of laboratory experiment, a microscopic sample of what would happen worldwide.”

As psychedelic elder James Fadiman reminded me “mushrooms don’t know they’re illegal.” Mushrooms of the magic variety grow all over the world in over 100 species. Mescaline occurs naturally in the peyote cactus, and DMT can be found in many plants and animals (possibly including ourselves). Since they’re naturally occurring, these drugs can’t be patented (related technologies, however, can). Drugs that can’t be patented don’t make for good business: Pharmaceutical companies can manufacture known drugs with ease. This low barrier to entry increases competition, driving down prices, leaving the companies with low-margin commodities. Psychedelics can also be effective in single sessions (whereas 60 percent of Americans on antidepressants have been on them for two years or longer) and may obviate the need for other pharmacological interventions. After all, is curing patients a sustainable business model? Combine these economics with the controversy attached to psychedelics, and it becomes easier to see why they were allowed to be criminalized.

Despite the apathy of big pharma, psychedelics are poised to re-enter the good graces of medicine. Psilocybin is in Phase II of FDA trials and recently received breakthrough treatment status for its promise in alleviating depression. MDMA therapy for PTSD is now in Phase III of FDA trials and could be approved and moved to schedule III as early as 2021.

There are four types of organization attempting to bring psychedelics to market: Big Pharma, venture-backed startup, nonprofit, and public benefit corporation.

Bloomberg Businessweek recently published a feature on ketamine, the anesthetic and club drug. While not traditionally considered a psychedelic, ketamine shares some similarities: it is well-known as a recreational drug, but has been discovered to be the best treatment for depression and suicide. Johnson & Johnson has patented a nasal spray form of ketamine, getting around the problem with selling old drugs:

“The pharmaceutical industry is not in the business of spending hundreds of millions of dollars to do large-scale studies of an old, cheap drug like ketamine. Originally developed as a safer alternative to the anesthetic phencyclidine, better known as PCP or angel dust, ketamine has been approved since 1970. There’s rarely profit in developing a medication that’s been off patent a long time, even if scientists find an entirely new use for it.”

MAPS founder Rick Doblin shared his excitement about ketamine with me, but noted that it works best in a therapeutic setting. Pharma companies don’t have much experience with therapy, he told me, their strategy is to find drugs that have an effect by themselves and sell as much of them before the patent expires.

The article creates cause for concern about price and access:

“Ketamine is considered a ‘dirty’ drug by scientists—it affects so many pathways and systems in the brain at the same time that it’s hard to single out the exact reason it works in the patients it does help. That’s one reason researchers continue to look for better versions of the drug. Another, of course, is that new versions are patentable….J&J hasn’t said anything about potential pricing, but there’s every reason to believe the biggest breakthrough in depression treatment since Prozac will be expensive.”

If Big Pharma were motivated to benefit the public, ketamine would be widely available at low prices, like generic, off-patent drugs. But, since their motivations are sometimes at odds with the public interest, pharmaceutical companies instead invest in making slightly different versions of drugs that already work but won’t be a cash cow. Ketamine is available in some clinics in major cities, but costs about $500 per infusion, pricing out people whose lives could be saved by a single session.

Can we expect better from younger rivals? Compass Pathways is the controversial startup that recently secured FDA approval for psilocybin as a breakthrough treatment. Originally a nonprofit, Compass has been criticized for capitalizing on the work of academic and nonprofit researchers to develop their business. A Quartz investigation describes how Compass courted researchers as a nonprofit, then iced them out and transferred its intellectual property to the company’s founders before transitioning to for-profit status. When a charity is dissolved, it is required to distribute its assets to other charities, a requirement Compass appears to have violated. The conditions Compass puts on research it sponsors are “restrictive contracts even by pharmaceutical industry standards, according to John Abramson, lecturer in health care policy at Harvard Medical School, and have the potential to distort the publicly available body of scientific knowledge.” David Nutt told me via email that this practice is “necessary under current commercial funding routes to [a] successful clinical trial outcome.” (The idea is that competitors could piggy-back off of Compass’s research and undercut the resulting products). The company only requires five days of in-person training for its therapists and does not require them to have personal experience with psilocybin. Katherine MacLean, one of the Hopkins researchers, called the short trainings “ludicrous” in our conversation:

“I saw near catastrophes happen, despite all the best preparation, an excellent medical team- [lead Hopkins psilocybin researcher] Roland [Griffith]’s team has been working together for 15 years- and still we were caught off guard. So my concern is people will be hurt.”

MacLean spoke to a larger attitude of downplaying some of the risks involved in psychedelic therapy:

“The things I saw just in four years at Hopkins- there were scenarios that I remember sharing with George [Goldsmith] and Katya [Malievskaia, Compass’s founders], and they’re like ‘oh, it would be best not to talk about those scenarios with the people who we’re trying to convince because it makes it sound way too scary,’ but it’s the reality.”

James Fadiman told me that he thinks Compass is attempting to control part of the psilocybin market, but they’re also trying to move things forward as fast as possible and get governments and insurance companies to cover the cost, which compares favorably with decades of SSRI treatment.

Rick and others in the psychedelic establishment (yes, there is such a thing) claim not to be worried about Compass. One reason Rick isn’t particularly concerned is that Compass has a competitor from Usona, a nonprofit that is also trying to do psilocybin therapy. The idea is, if Compass charges too much, Usona can compete. But Usona has struggled to get its own source of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) psilocybin, a requirement for FDA approval. Compass is trying to patent its method of manufacturing psilocybin, which could ensure that it has a significant cost advantage over competitors, who would need to develop their own means of making GMP psilocybin. The reality is that nonprofits don’t have many of the advantages of a venture-funded for-profit. To go through the FDA, an enormous amount of startup capital is required, erecting a large barrier to entry that nonprofits will struggle to surmount. MAPS needed to raise $27 million to take MDMA through FDA approval.

In an interview with Psychedelic Times, Doblin provides more context around the Compass controversy and disputes the significance of some of the claims in the Quartz investigation. He makes the case that Usona benefits from the work Compass is doing to change the public conversation around psychedelic therapy, and that Compass’s success in getting breakthrough therapy status from the FDA makes it easier for Usona to do the same. Rick argued for a wait-and-see approach to the short training time requirements, citing the fact that Bill Richards, the co-founder of the research program at Hopkins, is coordinating Compass’s research. Doblin believes that Goldsmith and Malievskaia were genuinely committed to the nonprofit path, but decided that they would not be able to secure the funding required to take psilocybin through the FDA (in contrast, Usona’s CEO Bill Linton founded the billion-dollar biotech company Promega and acts as the nonprofit’s primary funder).

Heffter Institute founder Dave Nichols told me that George Goldsmith is a “very human guy” with “high integrity”. That may be the case, but the integrity of a founder is less comforting than the legal requirements applied to nonprofits and public benefit corporations. Remember when we trusted Google’s unofficial motto: “don’t be evil”?

In December 2017, Bob Jesse authored the Statement on Open Science and Open Praxis with Psilocybin, MDMA, and Similar Substances: “From generations of practitioners and researchers before us, we have received knowledge about these substances, their risks, and ways to use them constructively. In turn, we accept the call to use that knowledge for the common good and to share freely whatever related knowledge we may discover or develop.” The nonprofits MAPS, Heffter, and Usona along with Doblin, MacLean, Fadiman, and over 100 other scientists, scholars, and practitioners have signed the statement; Compass has not.

The pushback to Compass Pathways is sometimes framed as the overreaction to the mainstreaming of a previously fringe movement: Compass is just doing business as usual in a space where business is unusual. Rick sees the entrance of for-profit players like Compass as a healthy sign for psychedelics: people think they’re a good investment. The allure of tax revenues and big returns helped legalize marijuana. But legal marijuana became quickly became commercialized marijuana, leading to some of the problems we face with alcohol and tobacco: powerful industry lobbies resisting regulation and misleading labeling and advertising. As one marijuana entrepreneur said at an alcohol industry conference, “I fundamentally believe that it is Big Alcohol and Big Tobacco that will be my future employer.”

Given the way for-profit companies have handled drugs, skepticism is warranted. Researchers, advocates and practitioners who have spent decades working to make psychedelics safely available to more people are understandably terrified of a company focused on the bottom line moving too fast and setting the movement back. Compass is running studies with 400 people in eight countries based off of research done with a very small group of people. Psilocybin poses psychological risks that MDMA doesn’t, and MAPS therapists undergo substantially more training.

At the same time, 300 million people around world experience depression, and Compass has moved faster than Usona. It may be the case that MAPS training and protocols are overkill, and that the Compass approach is safe and far more scalable and cost-effective. (The FDA has reviewed and approved the treatment and training protocols Compass has used). As Compass embarks on larger scale research, Katherine MacLean sincerely hopes for their success. For the sake of all the people who could be helped by psilocybin treatment, I do too.

The final approach may be the best we can hope for in the near term. An excellent series from Psymposia lays out the future of MDMA. MAPS has established a public benefit corporation that has the exclusive rights to conduct MDMA therapy for five years, should the treatment get approved by the FDA. The public benefit corporation is separate from MAPS, but MAPS is the sole shareholder. Any profits from the corporation go back into MAPS research, which is publicly available. From what I can tell, Rick is genuinely committed to making psychedelic therapy available to as many people as possible (MAPS has hired a patent lawyer to develop anti-patent strategies to ensure that nobody can patent the use of MDMA). The way to get there seems to be by jumping through expensive and onerous hoops to prove the safety and efficacy of psychedelics to the FDA.

There are still risks and drawbacks to the MAPS approach. If the FDA Phase III trials are successful, only MAPS’ GMP MDMA will be re-scheduled by the DEA. And legal risks for recreational users could persist as re-scheduling won’t necessarily change criminal penalties associated with the drug. For the five years that MAPS has a monopoly on MDMA therapy, only therapists trained by MAPS will be able to conduct therapy or trainings of their own, creating a potential bottleneck in the number of people who can legally provide MDMA-assisted therapy. The associated costs are considerable. Training for this therapy can cost more than $9,000. The current protocols for MDMA treatment involve many therapy sessions with a two-person co-therapy team that can cost up to $15,000 altogether. There are strict requirements on prospective MDMA-assisted therapy clinic: two MAPS-trained therapists, a prescribing physician who can obtain a DEA Schedule I license, access to a lab for bloodwork, and a cardiologist. Clinics must be established businesses with the facilities to meet therapeutic and security standards.

Thanks to these requirements, clinics are unlikely to pop up in medically underserved rural and urban areas, perpetuating historic inequalities. To help address this concern, the Open Society Foundation gave MAPS a grant to train therapists of color. Black Americans experience PTSD at higher rates than any other ethnic group, and all people of color are less likely to seek treatment than whites. FDA clinical trials are disproportionately white, a fact driven by unequal access to treatment centers, lack of time and money, and fears of exploitation due to the history of medical experimentation on black Americans.

Nick Powers is a literature professor who has spoken eloquently on the intersection of race and psychedelics, challenging the psychedelic community for its lack of diversity while acknowledging the enormous healing potential of the drugs. Nick told me that, in his experience, the psychedelic community hasn’t been hostile to people of color, “they’re burning sage, not crosses.” But the history of psychedelic usage has focused on middle-class whites, and black leaders like Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X have discussed how drugs were used as tools of social control, which helps explain why only 1 percent of people who go to Burning Man are black. Nick told me how psychedelics forced him to confront “glaring inconsistencies” in the black nationalism rhetoric he immersed himself in during graduate school. Like Malcolm X, Nick went to Nation of Islam meetings and converted to Islam. He learned to be anti-semitic and homophobic, but psychedelic experiences he had with a gay, Jewish friend “healed my bigotry and homophobia.” More will need to be done to make psychedelic inroads with communities of color, but the rise of events like the Detroit Psychedelics Conference is an encouraging sign.

Getting MDMA therapy covered by insurance is crucial to making it widely available to the people who need it most. MAPS is trying to prove to insurance companies that their treatment will reduce long-term medical costs that result from PTSD-related symptoms. If they are unable to do so, insurance providers will have no incentive to cover the therapy. Because they have to provide treatment and pay for disability for a lifetime, the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) is working closely with MAPS. Between 2010 and 2012, the VA spent $8.5 billion on PTSD treatment, a number that could be drastically reduced should the results of MDMA Phase II research generalize.

Once psychedelics return to the therapist office, they will hopefully return to respectability in the eyes of the general public.

Polling on psychedelics supports the wisdom of Rick’s approach. Overwhelming majorities of Americans oppose decriminalization of LSD and MDMA, let alone outright legalization. However, a 2017 survey found that a majority of Americans support medical research on psychedelics despite their legal status. When the surveyed group was told of the safety and effectiveness of psychedelic treatments, a majority reported that they would try the treatments if they were suffering from the treated conditions. In addition, there are efforts to decriminalize mushrooms in Denver and Oregon (a similar effort in California did not get enough signatures to qualify for the ballot in 2018). In contrast with Doblin, Dave Nichols told me that he doesn’t support outright legalization of psychedelics, but he does support decriminalization.

Following the model of marijuana medicalization and legalization, Rick believes in showing people scientifically how psychedelics can help people (and how safe they are). And following the model of the LGBTQ rights campaign, once psychedelic therapies are widely available, almost everyone will know someone who receives a life-changing psychedelic session. With the diminished social stigma, people will “come out of the psychedelic closet.”

Psychedelic Politics

In the 1960s, the powers that be grew to fear the power of psychedelics. The drugs’ ability to shake people out of their normal modes of thinking and to inspire people to question authority led to their targeting by the authorities and media. Nixon declared Timothy Leary the most dangerous man in America. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 classified LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline Schedule I drugs: those with a high potential for abuse and no medical uses. These drugs, and LSD in particular, became closely associated with the counter-culture, which nipped at the culture until the culture bit back.

But were these drugs the necessary and sufficient tools of revolution their most inspired advocates imagined? Does tripping acid turn you into a revolutionary? Was Nixon right to fear the High Priest of LSD?

LSD escaped the labs and therapist offices while the United States waged a monstrous war on the Vietnamese abroad and blacks at home. The same people who dropped acid were being compelled to invade a distant peasant society and conform to the stifling mainstream culture of obedience their parents embodied. Acid was closely tied with radical anti-authority figures like Timothy Leary, who boldly proclaimed “The kids who take LSD aren’t going to fight your wars…They’re not going to join your corporations…They won’t buy it.” The drugs took on the personalities of their loudest proponents. The collective experience of their users was in many ways a reaction to the challenges and anxieties of their times.

Psychedelics are like funhouse mirrors: They can cause you to see things differently, but what they reveal ultimately depends on who’s looking.

Martin Lee, one of the authors of Acid Dreams, told me, “these compounds don’t have a political point of view.” As his book demonstrates, the psychedelic 1960s were really a CIA experiment that got out of control. Both the hippies and the Agency saw enormous potential in psychedelics: as a tool for liberation and control respectively. Lee asked me “why is it that these substances have that responsibility attached to them? Why is it not good enough that these substances help people live a better life?”

Much has been written about the impact psychedelics could have on the way we treat mental health. If the early research generalizes to the overall population, we could live in a world where addiction, depression, PTSD, and existential anxiety are greatly diminished, if not eliminated outright. Given how much individual suffering these afflictions cause, this would be stunning progress in a stagnant field. When considering how these conditions relate to other social problems like crime and suicide, the possibilities seem nothing short of revolutionary.

But less has been written about what properly integrating these substances could do to our politics. Most of us do not suffer from severe mental illnesses, and some have argued that the transformative potential of psychedelics should be shared with everyone, not just the ill. This notion– what Bob Jesse calls the “betterment of well people”– is intoxicating. We may be looking for a panacea in the face of the seemingly insurmountable problems our species will face in the years to come. In the past we have been eager to find it in events (the fall of the Berlin Wall and the End of History), people (Obama, Trump, Bernie), and ideas (escaping to Mars, artificial intelligence). Are psychedelics the answer?

I am not the first to imagine an American politics where these drugs are embraced- in 1967, Timothy Leary boldly predicted: “Within 15 years, we’ll see an LSD orthodoxy. We’ll see an LSD president and a pot-smoking Supreme Court.” And in 1982, LSD had been a schedule I drug for twelve years and Nancy Reagan first told America to “Just Say No”.

The psychedelic pioneers I spoke to strongly related to the development of my own thought on psychedelics: initially a scary unknown that became the key to solving the problems of our world, before settling on the more measured conclusion that, while these substances are important, they are a part of a much larger, more complicated project.

The beginnings of a story of psychedelics as a panacea can be found in the famous Concord Prison Experiment, supervised by Timothy Leary while he was still a Harvard professor. The original study claimed that a single session with psilocybin reduced recidivism by over half and that personality tests recorded measurable positive changes. Rick Doblin conducted a follow-up study and found methodological problems, which, when controlled for, eliminated the claimed reduction in recidivism. In his conclusion, Doblin writes, “the failure of the Concord Prison Experiment should finally put to rest the myth of psychedelic drugs as magic bullets, the ingestion of which will automatically confer wisdom and create lasting change after just one or even a few experiences.”

Knowing that they are not a panacea, how might psychedelics actually change our politics? Three ways come to mind: individual personality and value changes occasioned by the drugs themselves, the societal impact of drastically decreased mental illness and addiction and corresponding crime, and the awakening to the politicized history of these drugs.

Psychedelic Minds

Beyond age 30, “Big 5” personality traits are fairly stable, any changes occur gradually and subtly. In a remarkable study of the effect of psychedelics on personality from Johns Hopkins, researchers found that a single high-dose session with psilocybin led to substantial and lasting increases to the trait Openness. Openness “encompasses aesthetic appreciation and sensitivity, imagination and fantasy, and broad-minded tolerance of others’ viewpoints and values” and is negatively correlated with traditionalism and positively correlated with universalism. Unsurprisingly, Openness is negatively correlated with a conservative political orientation. While the study involved a small sample, these results have no real precedent:

“During normal aging, Openness typically decreases linearly at a rate of approximately 1 T-score point per decade. In comparison, participants in the present study who had a complete mystical experience during their psilocybin session increased more than 4 T-score points from screening to follow-up. Notably, this increase is larger than increases in Openness seen in individuals treated successfully with antidepressant medication and intensive outpatient counseling for substance abuse.”

A massive meta-analysis of the relationship between personality and political orientation found that the degree to which Openness negatively predicts political conservatism in a given country is substantially affected by the amount of systemic risk, in this case measured by the country’s murder rate. The lower the murder rate, the more openness predicts liberalism. As the study authors note:

“These results suggest that a liberal political orientation may be thought of as (for lack of a better term) a relative luxury. People who are interested in novelty and, creativity (i.e., those who are high on Openness) tend to adopt a liberal political orientation. This tendency only emerges, however, when cues from the environment signal that the world is relatively safe, stable, and/or predictable.”

The range of possible applications for psychedelics in mental health treatment is so broad that predicting society-wide results is difficult, but some population-level research is promising. One survey found that:

“Lifetime classic psychedelic use was associated with a significantly reduced odds of past month psychological distress, past year suicidal thinking, past year suicidal planning, and past year suicide attempt, whereas lifetime illicit use of other drugs was largely associated with an increased likelihood of these outcomes.”

While, we cannot determine causality from surveys alone, the Hopkins study supports the idea that the psychedelic experience actually causes people to open their minds. The study occurred in a therapeutic setting, which likely contributed to the experience. But the survey and population data of users in a naturalistic environment suggest that, even taken “recreationally,” psychedelics can blow people’s minds into a more open shape.

While it is possible that the people who choose to take psychedelics are open enough to allow their minds to be expanded further, it could also be that those who shy away from illegal drugs would stand to gain even more from a psychedelic experience.

Psychedelics induce a similar effect to another kind of trip.

In 1966, Stewart Brand was tripping acid on his rooftop in San Francisco when a question came to him: “why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth?” This question, printed on thousands of buttons, along with a grassroots campaign successfully pressured NASA into turning the cameras around. Brand explained that the image “gave the sense that Earth’s an island, surrounded by a lot of inhospitable space. And it’s so graphic, this little blue, white, green and brown jewel-like icon amongst a quite featureless black vacuum.” This image and the resulting Whole Earth Catalog helped launch the modern environmental movement.

Brand intuited the power of something only experienced by a rare few. Astronauts who see earth for the first time from space report being deeply changed by the experience. The source of everything we’ve ever known and loved rests on a pale blue dot, suspended in darkness, clothed by a thin layer of atmosphere. National boundaries disappear and the fragility of our home becomes viscerally understood. This feeling is appropriately known as the overview effect. As we face down an unprecedented ecological crisis of our own making, the universalizing tendencies of psychedelics may help us remember that we are all mammals who have no other home.

Contrary to the beliefs of the petitioners trying to “Force Trump to eat shrooms until he realizes we are all one,” getting powerful people to experience psychedelics is not enough. Unfortunately, it is totally possible for elites to consume and greatly benefit from psychedelics and still believe that the masses aren’t ready or deserving of the same experience. Al Hubbard, the smuggler and spy who became the “Johnny Appleseed of LSD,” resented the mass embrace of acid psychedelic populists advocated. As detailed in Acid Dreams, Henry Luce, Time-Life’s president, was “an avid fan of psychedelics,” but also, “encouraged his correspondents to collaborate with the CIA, and his publishing empire served as a longtime propaganda asset for the Agency.” His wife, the great matriarch of post-war American politics Clare Boothe Luce, was fine with LSD use by the ruling class, but had a less than egalitarian view about the rest of the population, saying “we wouldn’t want everyone doing too much of a good thing.”

Psychedelic Society

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 66 percent of people in state prisons were dependent on or abused alcohol or drugs. Up to three quarters of people who begin addiction treatment report having engaged in violent behavior. Addiction has been criminalized since the days of Harry Anslinger. Following Portugal’s lead by decriminalizing all drugs would do a lot to reduce the crime associated with sustaining addiction. Going further and legalizing the most addictive drugs, as Switzerland did with heroin with great success, would do even more. In the absence of these changes, psychedelic therapy could dramatically reduce the number of people with addictions.

Crime or the perception of it can play a corrosive role in our politics. The actual rise in crime rates in the 1980s and 1990s contributed to a turn towards draconian “law and order” policies and rhetoric. In 1993, 9 percent of Americans reported crime and violence as the most important national problem, in 1994 that number jumped to 37 percent. This massive increase in public concern coincided with the 1994 crime bill, which subsidized state prison expansions, promoted mandatory minimum sentences and three strike laws, allowed 13-year-olds to be tried as adults, and further militarized the police. Low crime rates over the past twenty years likely contributed to the fact that only 1 to 3 percent of Americans have told pollsters that crime is the most important national issue in the years since 2002. Voters seem willing to roll back the worst excesses of the prison system based on their support for criminal justice reforms in recent state ballot initiatives.

Low crime is obviously not a sufficient condition for sane politics. The American murder rate was hovering around 50-year lows when Trump was elected. Low crime does, however, make things a lot easier. Americans appear to be open to alternatives to incarceration and harsh punishments when dealing with crime. Psychedelic therapies could offer a course of treatment to at-risk and incarcerated populations that actually help rehabilitate people, addressing a source of crime and showing the public that there are effective alternatives to punishment.

Psychedelic Awakening

Drug use and political radicalism go hand in hand. This is not due to some law of nature, but rather to the politicized criminalization of drugs. As the authors of Acid Dreams observe:

“The act of consuming the forbidden fruit was politicized by the mere fact that it was illegal. When you smoked marijuana, you immediately became aware of the glaring contradiction between the way you experienced reality in your own body and the official descriptions by the government and the media. That pot was not the big bugaboo that it had been cracked up to be was irrefutable evidence that the authorities either did not tell the truth or did not know what they were talking about. Its continued illegality was proof that lying and/or stupidity was a cornerstone of government policy. When young people got high, they knew this existentially, from the inside out. They saw through the great hoax, the cover story concerning not only the narcotics laws but the entire system. Smoking dope was thus an important political catalyst, for it enabled many a budding radical to begin questioning the official mythology of the governing class.”

In other words, if the government, media, and teachers lied about this, what else have they lied about?

The mainstream writing on psychedelic research often includes at least a passing sentence about the politically-motivated crackdown on these substances. The reality is that the people who played a role in the criminalization of psychedelics, the officials and journalists and doctors, have blood on their hands. Not just of the people who were imprisoned for violating drug laws, but of the millions of people who succumbed to their addiction or depression who could have been helped by a psychedelic session. Or the millions more who died anxious and terrified, withdrawn from the world and the ones who loved them. The architects and custodians of the war on drugs are the real criminals. To think otherwise, that they were well-intentioned but misguided actors, is to be ignorant of the racist, anti-intellectual history of drug prohibition. And those who inherited the drug war and sustained it had access to voluminous evidence that their war was based on none.

Psychedelics and the Future

America seems to be on the verge of embracing psychedelics.

The left focuses (correctly) on the real interests motivating the actions of those who wield power. Capitalists who control the mineral rights to a trillion dollars worth of fossil fuels oppose action on climate change for obvious reasons. We don’t need a complicated theory of political economy to understand why so many billionaires oppose higher taxes on their income. People respond to incentives, and we need to change the incentives. But different people respond to the same incentives in different ways. A turned-on world won’t automatically become a just one- there are no shortcuts to justice. But power is ultimately rooted in the minds of people. Changing minds changes power.

But psychedelics will not usher in the revolution. They are no substitute for political education and organizing. The insights brought on by the experience are not guaranteed to be true or useful. There are no shortcuts to justice or good politics. But psychedelics have unprecedented potential to make people’s lives better. And if the left should be for anything, it should be for making people’s lives better.

We are facing down the greatest challenges to the continued existence of our species in the short history of civilization. The provincial politics of the 20th century won’t allow us to survive into the 22nd. Runaway climate change, nuclear proliferation, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, and risks we’re unaware of could put an end to the human experiment. These are problems that will require global coordination, concern for future generations, and a universal outlook to solve—problems that require us to step out of our normal frames of reference. And there is no better tool for changing your frame of reference than a psychedelic.

Will psychedelics save us? Not by themselves, no. There is no replacement for a robust social safety net, a humane criminal justice system, and economic justice. But the problems that face us are enormous, and we’ll need all the help we can get.

This article was originally published in the January – February issue of Current Affairs.

Correction: This article has been amended to clarify that more Americans than initially stated are in favor of medical research into and medical use of MDMA and psilocybin. This article has also been amended to state that Compass Pathways requires five days of in-person training for its therapists, not a weekend as was previously stated and that the FDA has reviewed and approved Compass’s training and treatment protocol.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.