The Age of Trump began on June 17, 2015. That was the night of the Charleston Emanuel 9 massacre. Dylann Roof’s attack, which left nine African Americans dead and numerous more injured, reminded the nation at the height of the Black Lives Matter protest movement that the nation’s deadliest original sin—white supremacy—could strike African Americans anywhere, at any time. The response to that attack was, in some ways, sadly predictable: the immediate celebration of the group of the church’s members who forgave Roof for the attack; public praise for the “grace” displayed by African Americans in Charleston for said forgiveness; and Americans across the political spectrum praising the citizens of South Carolina for not protesting and rioting like their kin in Ferguson, Missouri and Baltimore, Maryland. (Never mind that the situations—a terrorist striking a historic African American church versus a lack of accountability for police violence towards African American citizens—were two entirely different situations.) But leading as it did to greater public pressure for the removal of Confederate monuments, the attack did also spark a deeper conversation: one about the very ways in which Americans conceive of their past—and by extension, their present. This legacy is still at the heart of the Age of Trump, a desire to question what makes America America. (And what would make it “great again,” and if it ever was.)

Trump’s America is, in many ways, a rejection of years of historical research and argumentation that have added necessary nuance to the history of the United States. Scholars have excavated historical truths that had been carefully scrubbed from public memory, from Columbus’ indulgence in routine torture that shocked the Spanish to events like the Negro Fort massacre in which Andrew Jackson’s troops invaded sovereign Spanish territory and killed several hundred free blacks. Today’s adults often learned from textbooks that either whitewashed or outright endorsed crimes against the black and native populations. The 1961 schoolbook Exploring New England, for example, describes the massacre of Pequot Indians thusly: “Soldiers killed nearly all the braves, squaws, and children, and burned their corn and other food. There were no Pequots left to make trouble… ‘I wish I were a man and had been there,’ thought Robert.” (In the book, Robert is a fictional white child learning the history of the region.)

When President Trump argued that attempts by activists to remove Confederate statues was a struggle to “take away our culture,” it was clear the “our” excluded large numbers of Americans. It was a noted contrast to Barack Obama’s remarks at the opening of the Museum of African American History and Culture: “…African American history is not somehow separate from our larger American story, it’s not the underside of the American story.” President Trump’s proud ignorance of American history needs a response—but African Americans have wrestled continuously with this problem, as they remind the nation of its darkest historical moments.

African Americans have long posed the question of what America is and the extent to which they can or should consider themselves part of it. It is at the very heart of the scholarly endeavor known as African American history. And while most Americans struggle to keep history at arm’s length, African Americans constantly fight to keep the past alive. Much of that past is deeply uncomfortable for most Americans to think about. For some, that past is deeply painful, which is precisely why it must be preserved and discussed.

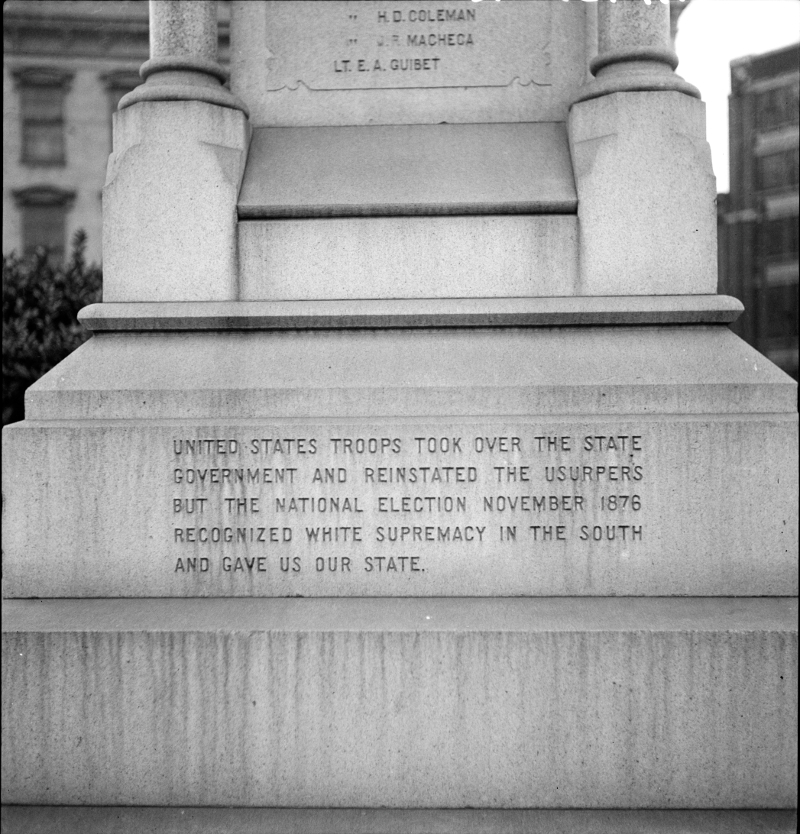

In each era, the kinds of American history being written are inextricably linked to contemporary problems. Fighting over history is fighting over modern politics. The Black Lives Matter movement taking up the cause of removing Confederate statues is a case in point. For them, the links between police brutality in the present, and the building of statues lionizing the Confederacy and immortalizing in stone heroes of white supremacy, were evident. (Sometimes the statues were explicit about what they stood for. One taken down in New Orleans, the Battle of Liberty Place Monument, celebrates the 1874 attempt by the White League to violently overthrow the racially mixed Reconstruction government. An inscription on the monument honors those brave men who fought on behalf of “white people” until the Compromise of 1877 “recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.” Anyone naïve enough to think these monuments aren’t about white supremacy should look more closely at them; in the case of the Liberty Place monument those very words are used.)

African Americans, and the American Left, have often fought to shift the discourse on history in the public sphere, and the presidency of Barack Obama had in some ways prepped the ground for the shift in thinking about history we’re seeing today. Obama couched the nation’s history in a story of progress and struggle. His 2013 inaugural speech mentioned American progress “from Seneca Falls, to Selma, to Stonewall,” three crucial events in the fight for women, African Americans, and LGBTQ people, respectively. Reflecting this emphasis, in the final days of his presidency Obama gave the approval for the first-of-its-kind National Park centered on the story of Reconstruction in Beaufort, South Carolina.

The Reconstruction period is important to understanding our current crisis of revived open white supremacy. Reconstruction, the time after the Civil War in which black Americans were briefly granted basic civil rights, and even held public office across the South (before white Southern “redeemers” successfully aborted the project and restored absolute white dominance), is often poorly understood by Americans. One example of how Americans still struggle with Reconstruction’s legacy occurred during the 2016 presidential campaign. Hillary Clinton, in answering a question about the president that most inspired her (Abraham Lincoln), gave an interpretation of Reconstruction that included elements of the older, “tragic history” narrative of the era. Clinton described the tragedy of Lincoln’s death as forgoing an era that “might have been a little less rancorous, a little more forgiving and tolerant” and which instead led to “Reconstruction, we had the re-instigation of segregation and Jim Crow.” It seemed the former Secretary of State ignored the genuine struggles of African American—and more than a few white—Southerners to forge a new, more democratic South in the post-Civil War years. This could not have been done without some “rancor,” but the actual era needed more federal backbone, and possibly more confrontation, to keep the promises of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to African Americans.

One hates to even imagine how Donald Trump likely sees the Reconstruction period, if he even knows what it was. As Matt Ford showed in his Atlantic essay, “What Trump’s Generation Learned About the Civil War,” school children in the 1950s and 1960s still learned about Reconstruction as a mistake, rather than as a small step in the direction of justice that was abandoned far too quickly. The subsequent civil rights struggles that continue to this day occur, and are necessitated, in part because Reconstruction was never completed. Much more needs to be done to help many Americans who haven’t taken an American history course in years understand why Reconstruction still matters now. There is a worrying disconnect between how historians view Reconstruction—as a missed opportunity for the United States to truly live up to its creed—and how most people outside the academy view it. They either ignore it as an important period in U.S. history, or continue to see it as a “mistake.” But leftists and African Americans alike have long understood this. Reinterpreting Reconstruction for a broad audience is key.

Such a reinterpretation has been done before, during other times of national crisis. The 1930s Left saw the Reconstruction era differently from the dominant American perspective. Viewing historical battles over the future of the South through a Marxist lens, many leftists began to see the period as the first—and up to the 1930s, only—moment of radical democracy in the South’s history. Bruce Baker’s What Reconstruction Meant shows that numerous historians, including several African Americans, tried to push back against the “Lost Cause” view of Reconstruction, which held that the attempt to give African American men voting rights and a proper stake in political debate was a failure and a mistake.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction in America was the most important work to reinterpret the Reconstruction period in the 1930s. For Du Bois, the Reconstruction era was a missed opportunity for genuine black-white solidarity. The book was also Du Bois’ way of staking a claim to African American humanity. If you grant African Americans some sense of political and social agency in the past, then you are saying they are human beings in the here and now, with their own fears and dreams that should be respected. This “usable past” was an attempt to not just educate, but to prod Americans in the 1930s to come together across the color line to change the country for the better. The stakes of the book were clear to Du Bois: African Americans were very much part of the historical narrative of the nation. He wrote a note to the reader at the beginning of Black Reconstruction in America which stated, “In fine, I am going to tell this story as though Negroes were ordinary human beings, realizing that this attitude will from the first seriously curtail my audience.”

By the 1960s, African American scholars and leftist historians continued to chip away at the old Reconstruction history of failed African American governance. African American history, which for years had had a considerable following among African Americans themselves, gained its widest popularity in the late 1960s. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, people wanted to understand Reconstruction to make sense of the last time African Americans had such a critical impact on American politics. Popular historians such as Lerone Bennett utilized popular media, such as Ebony magazine and various news programs, to get across the argument that African American history mattered.

“History is everything; it is everywhere,” Bennett wrote in his essay “Black History/Black Power.” “History to us is what water is to fish.” Later on in the same essay Bennett made the argument even plainer—for him, history was “knowledge, identity, and power.” Understanding the African American past was essential to African American existence in the present, because the present was unintelligible except in light of what had come before. This is also why, for instance, the Black Panther Party of Oakland, California wanted their members to read historical works. The required reading lists for the Panthers included works such as Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction in America and Souls of Black Folk; Herbert Aptheker’s American Negro Slave Revolts; C. Vann Woodward’s The Strange Career of Jim Crow; and John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom. These, and many other titles, were required reading for new Black Panthers to make sure they understood precisely the place of African Americans in the history of the United States. These books were necessary to help new members of the BPP realize that the education they often received in school—one that gave African Americans little more than a submissive role in American history—was erroneous and intentionally designed to give a false impression of the past.

These stories of African American resilience mattered during an age of white backlash. While we think of the Civil Rights Movement as a high point of black struggle for freedom, in reality they were also periods of heavy, sustained white backlash—north and south. Conservative publications loathed the demonstrators, with William F. Buckley’s National Review referring to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 as “mob rule.” But this view wasn’t just held on the right. The majority of Americans often disagreed with marching as a form of protest, and it’s easy (and convenient) to forget just how unpopular the movement was. Polls from the era show that whites overwhelmingly thought civil rights demonstrations were “hurting the Negro” and wanted them to stop. Northern liberals dismissed attempts at civil rights campaigns in northern cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago. To them, the problems with race and “de jure,” or legally sanctioned, segregation were in the South. The North’s problems were merely a symptom of “de facto” racism, created by customs and the desire of people to “live with their own.” African Americans knew better.

Another resurgence in attention to African American history took place in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Reagan’s America was built on the threat of turning back the progress made by African Americans since the 1960s. But early hip hop often made mention of the past, through songs such as “Renegades of Funk,” calling back to a proud past of struggle and resistance to tyranny, and movements such as the campaign to make Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday a national holiday kept alive the spark of the halcyon days of the 1960s. It took a national fight to get MLK Day recognized, and Southern states took their obstinacy to ludicrous extremes. (Until 2000, Virginia celebrated “Lee-Jackson-King Day” instead, which honored Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson as well.) Republicans who voted against recognizing Martin Luther King Day, such as Orrin Hatch, John McCain, Chuck Grassley, and Richard Shelby, are still serving in the U.S. Senate. Reagan himself only grudgingly agreed to recognize the day, having argued that “we could have an awful lot of holidays if we start down that road.” What animated the fight over King’s holiday was a realization, among activists across the left spectrum, that something was needed to show that the left still had a strength and purpose in American politics.

Films such as Glory and Malcolm X were also reminders of black bravery in the face of overwhelming white supremacy. Like Roots in the 1970s, these two films were callbacks to historical moments often misunderstood by most white Americans. Glory has the distinction of being one of the few Civil War films to state, without hesitation, that the war was sparked by and was about slavery. Malcolm X, while stripping away most of Malcolm’s internationalist outlook and his career of making common cause with anyone interested in fighting for freedom, was still a significant moment in the modern tale of bringing African American history to the masses.

Today, many historians have taken on the mantle of activist-scholar, a title held in the past by intellectuals like Du Bois, Lerone Bennett, Carter G. Woodson, and Howard Zinn. Today, historians such as Ibram X. Kendi, Keisha Blain, and Keri Leigh Merritt—among so many others—carry forward the idea of historians participating in critical debates in the public sphere. The African American Intellectual History Society, in which Keisha Blain, Kendi, and Ashley Farmer all have leadership positions, has become a key site, both online and through its annual conference, for thinking about the relationship of thorough and objective scholarship with the needs of modern political discourse.

Many of these historians have made clear the link between political discourse and remembering the past. Karen Cox, for example, pioneered studying how white women in the South created a pro-white supremacist memory of the past with her work Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. David Blight’s Race and Reunion made similar arguments about the intentional attempts by many white Americans, across the Mason-Dixon line, to whitewash the past and forget about both the causes of the Civil War and the national lack of will to properly push Reconstruction forward.

Pushing Americans to understand their own past means historians will have to continue engaging the public—whether it’s in op-ed essays, books written through popular presses, or hosting talks and seminars outside the walls of their local college or university buildings. It won’t be easy. But we have models for this—Carter G. Woodson’s engagement with African Americans through his Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) is a worthy example. Professional societies such as the Organization of American Historians are also trying to change this, with the magazine the American Historian aimed at non-academics. Their “Process: a blog for American history” page is similarly aimed at both academics and non-academics alike.

Dealing with the right-wing response to these historical arguments is also an important part of the debate over the American past. The defense of Confederate statues seems to indicate a failure to understand what gave rise to those statues. They did not grow out of the ground like trees or emerge from geological pressures like mountains. The statues are man-made totems to white supremacy, and the decision to put them up was made by white Americans across the South desperate to showcase their dominance over an African American population whose political and economic power had been curtailed by the collapse of Reconstruction in the 1870s and the completed rise of Jim Crow segregation by 1900. (Just as with the monuments, the Confederate battle flag, rarely displayed for many decades after the war, was revived and deployed when black social movements began to threaten white power. The Dixiecrats used it in 1948 to indicate their racial views, and Georgia added it to their state flag after Brown v. Board of Education.) This right-wing view of the past—best seen in Charlottesville in August 2017—holds that America has been a white man’s country, and for it to continue to be “great,” it must remain so.

Again, we can go back to the Emanuel 9 massacre. The extreme Right in America knows the history of the nation as much as the Left does. How else can one explain why Roof chose Emanuel AME—a church that has been a historic place of resistance for African Americans since its founding in 1816—as his target on that particular night? For that matter, the virulent defense of Confederate memorials by much of the conservative Right in America is a testament to how they understand the stakes of the past. In Charlottesville, the extreme right was even willing to utilize violence in defense of a memorial to Robert E. Lee, a man who personally beat his slaves, broke up their families, oversaw the massacre of surrendering black Union soldiers, and declared that slavery was worse for whites than it was for blacks.

We should be using the words of Americans from the past to counter the extreme right’s attempt to permanently canonize figures like Lee. Union leaders such as Ulysses S. Grant and George Thomas—a general from Virginia who, unlike Lee, fought for the cause of the Union—perfectly understood the stakes of the post-Civil War attempts by former Confederate leaders to re-write history. Grant wrote in his Memoirs:

The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United States will have to be attributed to slavery. For some years before the war began it was a trite saying among some politicians that ‘A state half slave and half free cannot exist.’ All must become slave or all free, or the state will go down. I took no part myself in any such view of the case at the time, but since the war is over, reviewing the whole question, I have come to the conclusion that the saying is quite true.

Likewise, General Thomas thundered against post-Civil War attempts by white Southerners to change the meaning of the war. After dismissing Southern attempts to whitewash the past, Thomas wrote that they tried to argue that “the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains.” Further, Thomas pointed out that their punishment could—indeed, should have been worse—“when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them.” Leaders of the Union war effort understood, better than it seems most major American leaders do today—what the stakes of the Civil War and Reconstruction were. They knew better than President Trump or his chief of staff John Kelly do what statues dotting the American landscape in honor of Confederate military and civilian leaders represent.

Also, commercialization of the past alone cannot save us. Malcolm X required money from prominent African American celebrities to be completed. The proposed United States National Slavery Museum could never find enough willing sponsors, and plans had to be scrapped. Martin Luther King, Jr. has been used as a salesperson for a variety of products over the years (most recently in a widely-mocked television commercial for Dodge trucks), and his holiday has become a milquetoast call for public service—divorced from the kind of radical political outlook that characterized King for much of his career. (A career that included staunch criticisms of the very milquetoast liberalism that now celebrates him, as in “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” King even denounced the social effect of car commercials… elsewhere in the very speech that Dodge used to promote the new Ram.) There is the danger that any historical figure or moment that speaks to America’s radical past will immediately be appropriated by the Right—or, more likely, by the moderate center, which has also done much to strip away the radical roots of the Civil Rights Movement from mainstream narratives about it.

A hunger for understanding the past informs much of modern discourse on the Left and among African Americans. The popularity of Ta-Nehisi Coates is based largely around his deft usage of American history to talk about the problems of the present. While some of the left may disagree with his prescriptions for healing what ails Black America now, no one can disagree with the power of his essays about the Civil War, the Civil Rights era, and America’s repeated failure to deal fairly with African Americans. The success of Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad or Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing both point to continued interest in understanding American slavery. African Americans are not flocking to these narratives to wallow in the pain of the past, however; they’re trying to keep alive those stories so that they can draw strength to face the problems of the present.

As a young boy, I recall being taught about the giants of the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks dominated Black History Month. Yet there was one figure whose historical form changed in every teacher’s hands: Malcolm X. For some, he was merely ignored to get to the giants of our idealized civil rights past. But for one teacher, in my eighth grade year, he was “bad.” I still remember it: Malcolm X was bad, and Martin Luther King, Jr. was good.

And I remember thinking, quietly, sitting in the front row: She’s wrong.

I’d never thought that about what any teacher had said before in class. But I just knew—knew—Malcolm wasn’t this bad guy that she made him out to be. I wasn’t entirely sure of what he stood for. I knew he was a proud African American man. I knew he stood up for others who couldn’t stand up for themselves. And I knew—beyond a shadow of a doubt—he was a good man. Folks should not be given a sanitized version of the past. But they should be allowed to work through the nuance of the past and understand that every historical figure was complicated in some way. Malcolm X was one of the most fascinating, complex, brilliant, committed individuals in the country’s history, and turning him into the “bad” counterpart to the “good” King not only presents a simple-minded fabrication of history and erases the man’s true character, but prevents us from engaging seriously with Malcolm’s life and thought in order to draw lessons from it.

Ultimately, historians are participating in a fight about competing narratives of the past. But African Americans have led the way in this fight for over a century, refusing to yield to an explicitly white supremacist interpretation of the past. This is a way of holding on to hope in dark times—thinking about what people in the past did about the oppression they had to face and endure.

This article originally appeared in our print edition. Get your copy today in our online store or by subscribing.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.