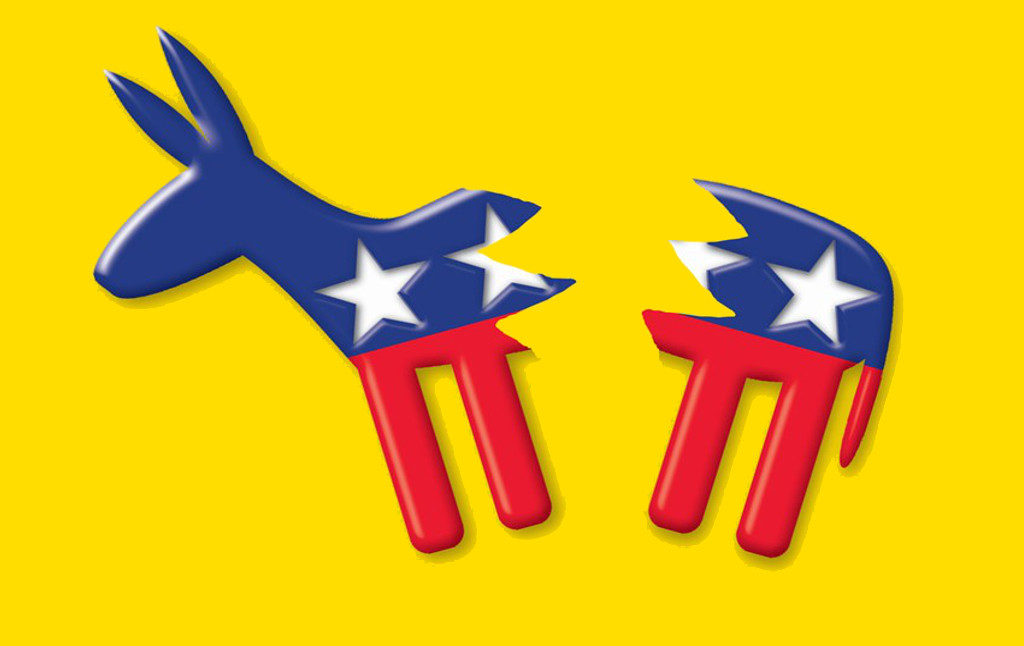

There is an old Will Rogers quip: “I am not a member of any organized political party… I am a Democrat.” Relative to Rogers’ time, the Democratic Party of today is much more organized. But here’s the catch: it is currently being organized into two different parties.

Roughly speaking, these two sides could be characterized as the “populist wing” and the “establishment wing” of the party, but even the divide’s terminology is a point of controversy between the feuding sides. The party’s left wing, for example, wants to call the conflict the “left-liberal divide.” Loyalist Democrats want to play down the divide, calling for unity on the grounds that Democrats are either (if they are younger, millennial types) all members of the Left, or (if they are older, Clinton-era types) all “liberals.” The Right, meanwhile, does not understand the divide, continuing to believe in a monolithic “radical left” filled with “radical liberals.” This leads to the funny situation, as one commentator noticed, where members of both the Left and the Right reach for the same “I made it through college without becoming a liberal” t-shirt.

The present conflict first surfaced, as many intra-party feuds do, during a presidential primary. But unlike past internal conflicts, this one is sticking around. John Kerry supporters, for example, did not take potshots at Howard Dean supporters deep into 2005. This year, however, a full ecosystem — replete with dueling podcasts, magazines, and candidates — has kept the divide alive. Skirmishes are popping up, like clockwork, every two weeks — from the DNC chair race, to the skepticism of Kamala Harris; from the launching of the Clinton-fawning Verrit, to the latest harangue from the liberal-bashing Chapo Trap House; and to every campaign, local (Jon Ossoff, centrist vs. Rob Quist, progressive) and foreign (Emmanuel Macron, establishment vs. Jeremy Corbyn, populist).

Discussing a resolution to this conflict is difficult, because even calls for “resolution” can be interpreted as ideological statements in and of themselves. Wanting the Democratic Party to survive and unify can be taken as an endorsement of the establishment, because the quickest path to intra-party peace is for the conflict’s left-wing instigators to get in line. Meanwhile, treating the intraparty divide as substantive and in need of “resolution” — arguing that there is, in fact, a significant difference between, say, Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren, or “Medicare for All” and “Obamacare” — can annoys liberals who believe that the so-called “divide” has been manufactured by a few disgruntled purists. Why, the liberals ask, do we need to “resolve” our differences with a constituency that lost the 2016 primary by 3.7 million votes and is led by a politician who does not even consider himself a Democrat?

To be upfront, I consider myself a member of what some have called “the Elizabeth Warren wing of the Democratic Party.” And if I wanted to follow the rule of most political commentary today, I would write something to be read by people who already agree with me— something to shore up my wing’s arguments, rally my wing’s passions and, if the situation calls for it, trigger the other wing’s anger. But here I am going to resist that temptation and discuss this conflict in a way that speaks to both sides of the divide.

Such cross-divide conversations are hard— and with the release of Hillary’s new book and Bernie’s Medicare for All bill, it is likely to get harder. But I believe in the old Mister Rogers maxim: what’s mentionable is manageable. In that spirit, I aim to persuade: to build up intra-party understanding by, first, doing my best to articulate what I believe each side feels; and, second, attempting to identify a few prospective patches of common ground.

Mapping the conflict: loyalty, strategy, and the party gap

To resolve our intraparty conflict, we must first understand it. We should look at what each side is concerned about: both what they say they are concerned about on the surface, and what they reveal themselves to be truly concerned about beneath the surface. I see these concerns clustering into three divides: the first over party loyalty, the second over how to win, and the third over the gap between Democrats and Republicans. Each cluster of divides may not be relevant to every partisan in the conflict, but most partisans have divided over at least one of these three.

The divide over party loyalty

Liberals accuse lefties of not being loyal to the party in general elections. This began with the vilification of left-wing third-party voters, such as Nader voters in the 2000s and Stein voters today. What made this past election special is that accusations of disloyalty were launched at a Democratic primary challenger. Clinton supporters feel that Sanders attacked Clinton excessively during the primary, stayed in the primary too long, and did not exert enough effort to support her in the general election. Many loyal Democrats around the country have analogous feelings about left-wing rebels in the party generally: they think criticisms should be kept inside the family and that it is important to be a “team player” to win elections and pass legislation. Some may call these loyal Democrats boring conformists, but from their perspective, it is party loyalists, not insurgent critics, who staff the party booth at the county fair and knock on doors every year to help get Democrats elected.

Lefties, on the other hand, believe this “disloyalty” accusation is bunk. First, they think establishment-wing leaders follow what Jon Schwartz has called The Iron Law of Institutions: “the people who control institutions care first and foremost about their power within the institution rather than the power of the institution itself.” Party leaders, they believe, care less about electoral and legislative victory than about maintaining their place in the party’s power structure. If party leaders were loyal to the party, lefties believe, then they would have learned from recent electoral losses and shaken the party up, even if it meant stepping aside themselves to make room for fresh faces and new ideas.

Secondly, insurgent lefties care less about catering to the dwindling group of grassroots party loyalists around the country, and more about activating the masses of non-voters and independents who are not yet loyal to any party. That is why they are less concerned about candidates, like Sanders, who are not technically Democrats: they see them not as selfish traitors, but rather as opportunities to build the party’s base. (Some liberals retort that there is a difference between appealing to independent voters and having a party leader who is not a member of the party.)

Loyalty to the party generally is often bound up in loyalty to party leaders. The party’s liberal wing tends to get excited about party leaders’ personalities and is more likely to share, say, Obama or Hillary memes, watch West Wing fantasies about party staffers, and follow the path of rising stars. This loyalty extends to the wider network tied to the party, too: to MSNBC personalities, party-aligned Hollywood stars like Meryl Streep, and liberal commentators.

Lefties thinks this level of loyalty is bizarre, especially when it comes to politicians they believe do not deserve it. They do extend loyalty to their own counter-establishment, sharing, say, Bernie-and-the-bird pictures and fawning over anti-imperialist heroes like Chelsea Manning. But lefties are generally less likely to express loyalty to leaders and more likely to pledge themselves to insurgent issue campaigns that bubble up from extra-party institutions, like labor unions or racial justice and environmental groups. They respond to liberal attacks of “Why aren’t you knocking on doors in the general election?” with “Why aren’t you joining the Fight for $15?” or “Why aren’t you campaigning for single payer?” Lefties believe liberals cannot think for themselves on issues—that they wait to get the go-ahead from the party establishment before they offer any support. To lefties, liberals’ shorter-term issues, like the Russia investigation, are just distractions if not embedded in more fundamental issue campaigns.

Establishment Democrats see lefties’ enthusiasm for disjointed issue campaigns over the party platform as further evidence that they do not understand “how real politics works.” As Slate writer Stephen Metcalf describes: “I see a social movement left that protests then goes home; and a Democratic Party that stays on and does the hard, boring work.” Loyal Democrats see their friends forming phone-banks to urge Congresspeople to oppose Republican attacks on Obamacare, and wonder why there are not more lefties pitching in. To loyal Democrats, either you call yourself a Democrat, be a team player, and move issues forward as part of a concerted, directed party strategy… or you believe in the power of, to use one common liberal phrase, “Bernie’s magic elves” who will mysteriously and effortlessly accomplish all the hidden work that it takes to make policy goals a reality.

Lefties, on the other hand, believe liberals have delusions of their own: namely that party politicians will naturally push important issues forward without any prodding. Who, the lefties wonder, are the magic elves who decide which issues are prioritized by the party? Party loyalists, they believe, fail to see that party priorities, absent popular agitation, are set by powerful interests. Lefties, they insist, are team players, but their teams are outside groups and issues, and they put in the work earlier in the policy process than establishment Democrats.

This divide over party loyalty played out in a recent skirmish over Kamala Harris, which began with a group of Democratic Socialists of America members starting a single-payer chant during one of her health care speeches. Liberals were disturbed, of course, that a group of non-Democrats were attacking a rising Democratic star regarding an issue not yet endorsed by the party. Party populists were disturbed by the liberal outcry because it was levied against a hard-working outside group engaging with a lever of political power over an issue of systemic importance to the Left. When Harris, weeks later, announced her support for single payer, her announcement was again seen through the lens of the conflict. Liberals saw it as an example of how lefties should have trusted a party leader to do what is right. The Left, meanwhile, saw it as demonstrative of their strategy: Harris endorsed single-payer because they protested her.

Jon Ossoff’s candidacy in Georgia is another example. Ossoff did not come out strongly for any issues that weren’t dictated by party leadership, but he was a loyal Democrat and would have been a reliable Democratic vote in Congress. His campaign was powered in large part by teams of suburban Atlanta moms— grassroots party loyalists who earnestly cared about resisting Trump. While liberals poured passion into the campaign, lefties criticized his milquetoast message. When Ossoff eventually lost, many party loyalists viewed it as another example of the Left not getting on board for a critical team project. Lefties, meanwhile, saw it as evidence that the party was still failing to understand the issues that really mattered to voters.

The divide over strategy

The divide over what we are trying to win is coupled with a divide over how we win. The first part of this strategic divide is over which policy moves a losing party should take to win back power. Liberals’ go-to strategy is often: if you are losing, tack your policies to the center of the electorate to win; once you win back power, you can enact what you want. As MSNBC host Joy Reid put it in July: “the way to see your ideals enacted is for your preferred party to gain and hold power… knowing that you had a large role in putting them there.”

Liberals like Reid believe that the Left too often chooses ideological purity over victory. (Just search “Nader + purity,” “Bernie + purity” or even “Warren + purity” on social media and scroll through the invective.) They think lefties are not serious about power: if populist leaders, they argue, ever had to actually lead the party — if they had to actually win elections and pass legislation — they too would be forced to be more pragmatic. Many establishment Democrats buy into the Republican talking point that America is a center-right country and that Democrats need to adjust their strategy to that reality.

Lefties have the inverse policy strategy: if you are losing, you need a more differentiated, passionate policy vision to win. The writer Adam Johnson explains how Corbyn succeeded with this strategy: “Corbyn’s campaign caught fire because he offered a clear moral vision of justice… they call it ‘ideology’ … But ideology is simply pragmatism over a longer time table.”

Lefties like Johnson believe liberals have been conned by the Right into playing on their rhetorical turf. When Democrats couch their proposals in Republican rhetoric — such as when they refer to Russian interference as “communist infiltration” or pitch social welfare programs as “helping entrepreneurs” — they, in the left’s mind, commit the double error of appearing like inauthentic Diet Republicans and diluting the power of the Democrats’ own potentially inspiring ideals. At their most skeptical, lefties wonder whether Democratic leaders are tacking to the center not simply as an electoral strategy, but because they actually do not believe in left-wing ideas in the first place. These lefties point to examples of times when Democrats had power and still did not advance their stated ideals in what lefties considered to be a sufficiently ambitious manner.

In short, the party’s liberal wing believes winning leads to idealism, whereas the party’s left wing believes idealism leads to winning. Thus lefties were dumbfounded why Clinton would, during an election, propose thousands of pre-compromised proposals aimed at passage through a Republican-controlled Congress, and, in turn, liberals were dumbfounded that Sanders would propose policies that required a “revolution” to become law at a time when the Democrats had not even won back Congress yet.

This ‘pragmatism vs. idealism’ divide extends beyond policy to the party’s fundraising structure, as well. Lefties see corporate campaign fundraising as similar to policy dilution: it prevents the party from drawing contrasts and harnessing the idealism needed to win elections, allowing Republicans like Trump to say “everyone is corrupt, so vote for us.” Liberals see this fundraising purity as a form of unilateral disarmament against the corporate-funded Republicans. They have more faith that Democratic politicians are ideologically unaffected by corporate fundraising and therefore wonder why Democrats should turn down harmless donations that support the worthy cause of winning back power from Republicans. We should save the corporate clean-up, liberals argue, until after Democrats are in power again. Again, the operative question: What first… winning or idealism?

The divide over the gap between Democrats and Republicans

Perhaps the root of these first two divides is a third divide: how much difference lefties and liberals believe there actually is between Democrats and Republicans.

Party loyalists believe the gap between the two parties is huge. The Republican Party is so egregiously horrible, they argue, that it is imperative to remain loyal to our only hope of stopping them: the Democratic Party. This viewpoint is captured in a recent Democratic Campaign Coordinating Committee sign reading “Democrats 2018: I mean, have you seen the other guys?” This belief that “the other guys” are so self-evidently awful on a scale that massively dwarfs any run-of-the-mill political mistakes the Democrats may have made explains why liberals tend to focus intensely on the outrages of the “other guys” — Fox News race-baiting, hypocritical Evangelical preachers, and old Jon Stewart clips about stupid remarks by Republican politicians — and downplay the left-liberal divide: given the constant threat of Republican power, any of our internal differences are miniscule. Additionally, the threat of Republican power, liberals point out, is especially acute to marginalized communities: whereas privileged idealists can afford to say “it has to get worse before it gets better,” DACA-protected immigrants at risk of deportation, black communities at risk of police brutality, and gay couples at risk of having their rights rolled back do not have the same luxury.

Lefties, on the other hand, sees the gap between Democrats and Republicans as smaller. They like to point out examples of silent bipartisanship: say, the complicity of Democrats in the disastrous war in Iraq and racist War on Drugs, or the Obama administration’s continuation of Bush-era corporate-driven education reform. They criticize party loyalists for letting Democratic leaders steer them towards formerly-Republican positions, such as when some Democratic loyalists began criticizing administration leakers like Chelsea Manning— a figure they would have lionized if she committed her leaks while Bush was president.

Behind this divide is a failure to see eye-to-eye over certain larger narratives— narratives that lefties talk about more than liberals do. The left often situates both parties within broader conceptual frameworks, such as neoliberalism, corporate power, and imperialism. To defeat these larger, nefarious societal structures and historical trends, lefties argue, we must identify them and prepare a plan to conquer them — a task more difficult than just defeating the Republicans at the ballot box.

Many liberals, meanwhile, either have not thought about, do not believe in, or do not prioritize addressing these forces. Some have even made fun of lefties for talking too much about “neoliberalism”— a phrase that many centrists believe has no meaning, but that lefties insist is analytically useful. (Ironically, this is the same dynamic at play when conservatives snarkily dismiss phrases like “white supremacy” and “patriarchy” as being meaningless, despite the insistence by both leftists and liberals that you could fill an entire library with books explaining each phrase’s depth of meaning.)

The criticism of Glenn Greenwald and The Intercept is representative of this divide. Liberals perennially accuse Greenwald of being easier on Republicans than on Democrats. And it is true that The Intercept likely gets more hits on articles about Democratic corporate corruption and Obama administration drone strikes than on Republican corruption or militarism. Yet lefties respond that Greenwald is addressing something larger than “Democrats vs. Republicans”— he is showing Democrats how their leaders are complicit in the odious forces they typically associate with Republicans. This strategy, lefties argue, is more effective at defeating, say, militarism and corporate corruption (since left-leaning people tend to care about these issues) than the much more improbable task of convincing Republicans that their leaders’ complicity in such forces is worthy of concern. Liberals worry that such critiques are feeding into Republican talking points and fuzzing the gap between the parties. Lefties, in turn, worry that harping on Republican misdeeds as if they were unique and unprecedented blinds us to our own leadership’s wrongdoing.

From divides to tribes

These divisions may have started the left-liberal conflict, but what has sustained the conflict has been the fact that because both sides are developing into integrated political tribes. As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues, political tribalism begins with shared intuitions: we first feel what is politically right, then later muster arguments to support our intuitions. When people who share some intuitions about politics find each other and discover they share other intuitions, they begin to form political communities to collaborate on mustering arguments for their shared bundles of political intuitions. Out of these political communities emerge leaders and institutions that further surface and solidify their connection and creed. The tribal formation is complete when these communities establish a unified tribal narrative— complete with stories of the past, present, and future; heroes and villains; and direction for what members should be doing. At its most extreme, tribal participation approaches a religious experience, as theologian Harvey Cox explained well in The Secular City: “In secular society politics does what metaphysics once did… It brings unity and meaning to human life and thought.”

Today’s left wing of the party emerged as a bundle of intuitions about the Democratic establishment: skepticism of the Clintons; concern about the Obama administration’s response to the financial crisis and wars in the Middle East; and curiosity as to why working class issues have been less trumpeted by the party in recent decades than they might have been in the past. In recent years, leaders and institutions emerged to articulate these intuitions: media ventures like Jacobin, the Intercept, and Chapo Trap House; politicians like Keith Ellison, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders; and organizations fighting for causes like a $15 minimum wage, Medicare for All, and a fracking ban. A narrative has coalesced of a party that has been corrupted by corporate campaign donations; is complicit in conservatism’s rise, through its capitulation to Reaganomics and Bush-era militarism; has displaced its working class base to make room for a professional, managerial class; and, finally and most damningly, has replaced its democracy-enhancing New Deal ambitions with a minimalist grab-bag of meritocracy-enhancing, technocratic band-aids.

The loyalist wing of the party has had a tribe-building process, too — one likely accelerated by the party rebels’ rise. They started out with a different bundle of political intuitions: more trust for leaders like Obama and Clinton; more credit given to what Democrats were able to accomplish in the age of conservative ascendance; more inspiration taken from the racial and gender diversity of party leadership; and more appreciation for the set of modern progressive causes the party has begun to articulate over the past decades. A network of party-friendly institutions, journalists, and leaders, old and new, has emerged to articulate and defend these liberal intuitions: media entities like MSNBC and Slate; the Democratic National Committee itself; the leaders and staffers of the Obama administration and Clinton campaigns; mainstream liberal think tanks; and prominent writers like Paul Krugman, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Chait, and Clara Jeffery. A narrative has emerged to unify this wing as well: a story that casts the Democratic Party as the entity that has overcome unprecedented Republican attacks to give voice to and fight for the interests of marginalized people in American politics.

These political tribes build a network of trust between their individual members and the complexities of national politics. As individuals, we cannot know everything about national politics, but what we can do is collect trustworthy people who do know about different areas of politics. Take Elizabeth Warren, for example: lefties believe she shares their deep politics regarding Wall Street, so they look to her when they want to know, say, if a recent regulation is effective or toothless. Or take Barack Obama’s foreign policy: many liberals are less critical of it than lefties are, because they trust that Obama is similar, deep down, to them, and therefore believe his decisions would be similar to the decisions they would make if they were privy to his information. Trust explains why each side is preoccupied with showing how different surface-level moves by national figures are windows into some alien — or familiar — deep politics: it validates their trust or distrust in each side’s establishment or counter-establishment.

These political tribes have their benefits. They help draw people into politics, bring people together and give members purpose. They ensure a range of political commentary: left-wing media tends to discuss long-term structural issues, while liberal media tends to zero in on upcoming elections and key Congressional votes. Tribes also provide platforms for new ideas, such as when Medicare for All first gained steam inside the left wing of the party and then broke through to the entire party.

But political tribalism can also be hazardous. At its worst, it creates enemies out of neighbors, turning complex people into “sell-outs” or “purists.” Tribes trick us into thinking that political participation is about being well-versed in tribal rhetoric — say, being able to list off the correct takes on past inter-tribal skirmishes — rather than about pursuing tangible goals. They encourage confirmatory, self-validating thought, rather than the exploratory thought that helps our politics stay aligned with reality. The focus that comes with tribalism can lapse into myopia, such as when some liberals can see Trump’s wickedness regarding immigration so clearly, but were unable to support immigration activists protesting Obama, or when some lefties can see the corporate corruption of Democrats so clearly, but fail to articulate the massive gap in corruption between the two parties.

A final danger of political tribalism, one specific to the intra-party divide, is that it is a danger to the coalition-building required to gain power through electoral politics. If a party coalition is divided against itself come Election Day, it may not stand. And if the coalition loses, both tribes lose. And with each passing of month of Trump-Ryan-McConnell rule, the stakes get higher and higher.

Resolving the conflict: toward vigorous critical loyalty

So, who’s right? Fortunately, a peace process, unlike a surrender ceremony, need not declare one side’s narrative as supreme. However, it does require each side to come to terms, at least a bit, with the best insights of the other side.

The liberals’ best insight is that today’s Republican Party — relative to history and relative to today’s Democratic Party — is an exceptionally dangerous political organization. It denies catastrophic climate change, is an almost-pure vessel for the corporate takeover of public power, has based its electoral coalition on aligning with white ethnic nationalism and authoritarian theocracy, and has instigated disastrous decision after disastrous decision over the past decades, from a war in Iraq that has left tens of thousands dead; to the mass incarceration that has decimated millions of American families; to the appointment of Supreme Court justices who have drastically shrunk the public’s power within the legal system.

Democratic Party leaders over the past decades may have been cowardly in the face of Republican cruelty — they may have even at times supported vicious policies aimed at appeasing Republicans or preventing Republicans from wooing over Democrats’ own reactionary constituencies — but they were, for the most part, not the instigators of the most callous developments in modern American politics. The pursuit of the destruction of the Republican Party as a force in American politics by any group even slightly more humane than them is a political project worthy of our support. Winning general elections against the Republican Party matters — and putting in the work to defeat the Republican Party at the ballot box is a responsibility of all progressives.

The lefties’ best insight is that the end-goal of electoral politics is not winning; it is the advancement of certain programs and policies. Party loyalty, the lefties correctly argue, may be good for winning elections, but it does not automatically translate into party leaders advancing party members’ desired causes. As anyone who has watched the conservative ascendancy within the Republican Party over the past decades knows, internal criticism of party leaders — backed by the threat of electoral insurrection — is what makes leaders listen. As Frederick Douglass said: “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” This is true not just of tyrannical enemy power, but also the power of leaders whom we happen to admire and respect.

A productive peace process for the intra-party war would merge these insights, advancing a practice that would help defeat the Republican Party while keeping Democratic leaders on their toes. We could call this practice “vigorous critical loyalty.” Vigorous critical loyalty would work by separating the times for vigorous party loyalty and the times for vigorous internal criticism. A Democrat practicing vigorous critical loyalty would, near the general election or a critical vote in Congress, demonstrate vigorous loyalty to the party, mustering support for the Democratic candidate or bill while holding criticism for later. But during a primary campaign and during ordinary legislative time, a vigorous critical loyalist would fight vigorously for her ideals, unafraid of criticizing party leaders, supporting primary challengers, and advancing outside issue campaigns.

For this to work, both sides need to give a little. Liberals need to accept that primary challenges to beloved party leaders are not only legitimate, but desirable so as to keep the party aligned with its people. A healthy party would have primary challenges for most of its elected officials — including Congressional leaders like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer — so that party leaders do not rest on their past laurels.

Liberals also need to accept that outside issue campaigns are legitimate. If an important issue — such as immigrant rights, civilian casualties from drone strikes, and true universal health care — is having a difficult time breaking through to the party, interrupting speeches and writing harsh critiques of party stars becomes necessary. Liberals should balance their loyalty to party figures with respect for this difficult, messy — and effective — work of pushing peripheral issues onto the national stage.

Lefties, on the other hand, first need to bring their political passion into mainstream party projects — especially general election campaigns. They should supplement their respect for the ideological fighters working hard to push important issues into the party mainstream with respect for the middle-of-the-road, grassroots Democratic rank-and-file who make sure that the mainstream has enough votes in Congress to make any policy work matter. Rebellious primary challenges and issue campaigns would be seen as more legitimate by grassroots loyalists if they saw that the same people launching them were as passionate about preserving Democratic Party power as they were about reforming its use. If lefties are asking liberals to respect the distinction between lefties and liberals, they should return the favor by respecting the distinction between liberals and their Republican adversaries— and act on that distinction by taking seriously the role the Democratic Party has played as, at the very least, a partial bulwark against the extremes of Republican power.

Second, lefties need to understand that the way to gain the respect of the other half of the party — not the insiders they do not care about, but the rank-and-file they do care about — is to not just say they “would have won,” but rather to actually win. The biggest problem with the Sanders campaign is actually the same problem that the Clinton campaign had: it lost. In turn, the biggest asset of the Sanders campaign is that it almost won. Obama was able to change the party because he won. The Fight for $15 was able to change the party because it has won in cities and states across the country. A rebellious vision gains followers when it shows it can win.

In sum, an ideal Democratic Party would arbitrate internal divides through a flurry of vigorous issue campaigns and primary challenges during ordinary time and then, during general election time and critical Congressional votes, rapidly unify to win.

This would move our conflicts — over which candidates are worthy of trust, over what voters actually want, and over the reality of certain larger forces — away from the neverending shadow-boxing ring and toward resolution in the court of public opinion. Primaries, for example, will help resolve the strategy divide, surfacing whether “pragmatism” or “idealism” wins in general elections, as candidates of different persuasions win primaries and test their pragmatist/idealist orientation in general elections. Issue campaigns, meanwhile, will surface the extent to which the party has been corrupted by nefarious structural forces. One need not endlessly discuss whether this or that politician is a “neoliberal shill” if you can resolve the question by launching issue campaigns that dramatize these larger forces at play and see whether said politician supports the campaign. If they do, they may be worthy of more trust. If they do not, they may be worthy of a primary challenge.

And finally, by agreeing from the start that everyone, no matter their level of criticism during ordinary time, is fully on board to support the party when general election time comes, concerns about party loyalty are reduced. All intraparty fights are tolerated — and even encouraged — because everyone can trust that we will be unified when it counts.

Vigorous critical loyalty presumes that people can change and that there is a potential to re-integrate, at least at the grassroots level, the left and liberal tribes. As issue campaigns gain support from current party leaders and improbable primary challengers become party leaders, party skeptics become more loyal, while party loyalists start showing loyalty to leaders and issues formerly seen as heretical. Constant issue campaigns and primary challenges keep leaders and issues churning in and out of the party’s center, preventing party leadership and orthodoxy from stagnating while, all the while, a commitment to active general election loyalty keeps the party unified so that this churn does not pull the party apart.

Most importantly, vigorous critical loyalty could help rebuild trust. Primary challengers that win — and even incumbents that are forced to hold back a primary challenger — become closer to the people they represent. To have an issue emerge from a trusted outside group and then have that issue enter the mainstream of the party is to build loyalists’ trust in that outside group while building populists’ trust in the party. With the periphery of the party showing loyalty in the general election and the center of the party opening up to new ideas and leaders, the distinction between the periphery and the center is blurred.

This is how two tribes could eventually merge into one without either side compromising on their ideals and loyalties. Reading Twitter today, it may seem like a longshot. But I take hope from a point Washington Post assistant editor Elizabeth Bruenig raised at a talk earlier this year: “You don’t argue with people who are nothing like you… you argue with people who are almost like you… [Arguing] is a pretty good sign of the possibility of coalition.”

So the next time you find yourself arguing with a friend from the other side of the intraparty divide, take solace in the fact that your bickering means there is, in fact, still hope for a left-liberal coalition. Before that bickering turns to silence, we may, with the practice of vigorous critical loyalty, be able to transform it into a just unity and, critically, a prompt victory.